When I wrote Part One (30 May 2015) I was aware that E.T.B. Francis had written an account for the University of the first field trip to Rovinj, then in Yugoslavia, from Sheffield’s zoology department. I had written up a report on the reptiles and amphibians we found during the afternoons we were not in the lab, out and about doing the marine biology or visiting places of wider interest. He caught me in the corridor to say that he had sent the report in to the university’s Gazette. However, until a couple of months ago I had not seen what he had written. Then I found on eBay a copy of the Gazette published in October 1964. When it arrived I was pleased to see that it contained the article. With it in hand I have been able to put names to places we had visited and to draw a map and after further Google searches, to caption more accurately the photographs I had taken. At the end of this article I have also added a series of explanatory notes.

First though, I should remark that the trip to Rovinj was revolutionary for the early 1960s. Language students had to spend time abroad but for undergraduate science students a field course in continental Europe was something very special.

|

| Rovinj Marine Laboratory |

This is Francis’s complete account from the Gazette:

ROVINJ, EASTER 1964

For many years past it has been a tradition amongst zoological departments that honours students should spend some time during the Easter vacation at a marine station to study ecological and faunistic problems associated with animal life in the well defined habitats of the sea shore and shallow seas. Such students, at the same time, get the valuable experience of examining and identifying living animals collected personally from their natural habitat.

Considerable emphasis has always been placed on the importance of such studies by the department of zoology at Sheffield, but this year a difficulty arose since the laboratory at Robin Hood’s Bay belonging to the University of Leeds—to which the second year honours students would normally have gone—is in the process of rebuilding and enlargement and was therefore unavailable. Accordingly Professor I. Chester Jones decided on a bold experiment and set arrangements in operation which resulted in a party of 31 students and 7 staff travelling to Rovinj where the Jugoslav government has a research station on the Istrian coast of the Adriatic.

Two laboratories, one large and one small, were made available by the Director of the Station, Dr. D. Zavodnik, and the Station’s research vessel. Bios, was chartered on several occasions. Thus it was possible to study the faunas characteristic of several types of substratum—hard bottom, secondary hard bottom, sand, mud, shingle—found at moderate depths off shore, as well as the littoral fauna of the shore itself. The use of the Bios also enabled samples of plankton to be collected and studied, thus giving the opportunity to examine forms, both larval and adult, specially adapted to a floating life at the surface of the sea.

The fauna as a whole proved exceptionally rich, both in quantity and quality, northern species such as are found round the coasts of Britain mingling with others characteristic of Mediterranean waters, the one sometimes supplanting the other in characteristic ecological associations.

Morale and enthusiasm were high: staff shared with students the excitement of examining alive species which had hitherto been unknown, even to the most experienced members of the party, outside the pages of specialist textbooks. Over 180 species were individually identified and at least seven or eight new records were added to the fauna lists. It is very doubtful whether so rich a zoological experience could have been obtained in the same period of time around the shores of Britain—certainly not from one station alone.

In addition to the faunistic work a serious and extensive study was made of the speciation of the limpets occurring locally, including a chromatographic analysis of their pigments, in order to compare the forms found at Rovinj with those previously studied in former years from British waters. The Jugoslav government has a station for the culture of oysters and mussels at Limski Fjord, some eight miles north of Rovinj, and the party was able to visit this and to see something of the techniques used.

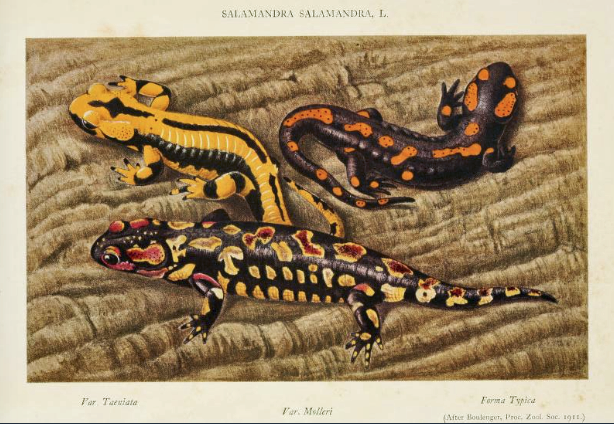

As a side-line two devoted herpetologists in the party spent every spare moment of their time in the study and collection of the local amphibia and reptiles. In all they captured some 103 individuals comprising four species of lizards, four species of amphibia and one species of snake.

Outside the strictly zoological purposes of the excursion, occasions were made to take advantage of such cultural opportunities as the neighbourhood offered. Thus the party took a day off to visit Venice, travelling each way by a specially chartered bus and spending five hours in that unique city. On another occasion a half-day was spent visiting the ancient Roman city of Pula, where there is still a well preserved first century amphitheatre attributed to Augustus, and other relics of Roman times. Even the coach journeys to and from the railhead at Ljubljana on the outward and homeward journeys were utilized. The limestone caves at Postojna were visited on the outward journey. These are famous not only for exceptionally fine stalactite and stalagmite formations, but also as the home of the blind cave-salamander, Proteus anguinus, which the party was able to see alive. On the homeward journey a stop was made at the deserted medieval village of Dvigrad near Kanfanar to visit the church of St. Anthony and to see the very fine and vivid fifteenth century frescoes, and at Porec to visit the sixth century basilica of St. Euphrasia with its fine mosaics, comparable with those of Ravenna in brilliance.

This remarkably successful expedition would have been impossible but for the enthusiasm, energy and organizing ability of Dr. F. J. Ebling, who not only planned the whole enterprise beforehand, but shouldered the day to day responsibility for its successful conclusion. He deserves great credit and the gratitude of all who benefited from his efforts.

At the Rovinj end the way was prepared by Anton Perusko and his wife Gillian (nee Gillian Glen, B.Sc. Sheffield 1959). In spite of having to care for two young children, Gillian Perusko met the party at Ljubljana and escorted it to Rovinj and throughout the whole visit acted as general guide, interpreter and liaison officer. Anton Perusko made use of his official connexion with the “Auto-Kamp” Enterprise to smooth away many spiky corners connected with the accommodation, transport and such like matters. Without their invaluable help and full co-operation the venture could never have succeeded or even been contemplated.

Much friendliness and co-operation was shown by Dr. Zavodnik and his staff at the laboratory as well as by the staff of the “Jadran” Enterprise at whose hotel the party stayed. At the Jadran Hotel it was introduced to many interesting national dishes; in fact, with the exception of milk-fed lamb, which is traditional for “Big Friday” and Easter Day, no major dish was repeated on the menu throughout the whole period. In the interest of international relations the Jadran Enterprise organized a dance on Easter Saturday to which many local people came to meet the English party of whom they had been told by the national radio and press.

Valuable as the zoological assets of the excursion proved to be, it is clear that these are by no means the only entries on the credit side of what must remain for all who participated a most memorable experience.

E T B Francis

The Places

My Photographs

I took my ‘Baby’ Rolleiflex 4 x 4 camera. This took 12 exposures on 127 size film. I used Agfacolor CT18 reversal film which is now known to be prone to degradation with time and to be ‘grainy’. Differences in processing may be partly responsible for the poor long-term reputation of this film. Unfortunately, despite being stored in identical conditions, the Rovinj films have survived amongst the least well of the photographs I have stored. The film base has warped, false colours have crept in from the edges and some have faded.

The Journey from the Hook of Holland to Ljubljana via Munich

|

| The Rhine from the train to Munich |

|

| Vineyards in Germany from the train |

|

| Vineyards from the train |

|

| Somewhere in Austria from the overnight train from Munich to Ljubljana |

We had several hours in Munich on the way out. The two of us wandered out of the station and found a beer hall which Google Earth shows to be Augustiner Stammhaus. We had steak and chips with, of course, beer. I was in the same establishment seven years later for a dinner during the International Physiological Congress. More beer was consumed.

Postojna Cave

(2 slides I bought)

Rovinj

|

| M/V Bios - the research vessel |

|

| Rovinj: Hotel Jadran (Adriatic) centre |

|

| Rovinj from the Bios |

|

| Rovinj |

|

| Rovinj |

|

| Rovinj. The shop on the left sold filigree jewellery for which what is now the Croatian coast is famous. My wife brought the bracelet (below) |

Pula

Venice

|

| The Sheffield party in St Mark's Square |

|

| We travelled to and from the bus by vaporetto |

Limski 'fiord' north of Rovinj

Film Set for The Long Ships (filmed in 1963) near the end of Limski 'Fiord'

Dvigrad

|

| Church of St Mary of Lukać |

Unwelcome Fauna

My wife’s (then girlfriend) abiding memory the Rovinj trip is arriving back with an unwelcome guest. She left the party at Harwich since her parents were living in Suffolk. Drying herself after a bath she though she had developed a new mole. Closer inspection revealed a large blood-swollen tick. She blamed—and still does—the Munich-Hook of Holland sleeper.

Notes

- The 31 students were the 2nd years honours group plus a few from 3rd year.

- The staff were F.J.G. Ebling, E.T.B. Francis, O. Lusis, J. D. Jones, D. Bellamy, L. Hill plus Mr Hancock, the chief technician.

- D. Zavodnik was one of the authors of the history of the Rovinj laboratory.

- The hotel we knew in Rovinj as the Hotel Jadran was originally called the Adriatic. It has been refurbished and is again known as Hotel Adriatic.

- Not mentioned was the visit to the film set built for The Long Ships near the end of Limski ‘fiord’. I read that it is now fallen down. However, The Viking Restaurant was built on the site by the film’s caterer and can be found on Google Earth. It is accessible, as was the film set, by road.

- The deserted medieval village of Dvigrad is now a major tourist site. My photographs are not in the church Francis mentioned but in the Church of St Mary of Lakuć.

- Dates, as mentioned in part 1, the date of entry into Yugoslavia was 17 March with departure on 1 April. Remembering the journey, we must have left Sheffield on 15 March and returned, carrying the microscopes we had taken with us, on 3 April.

- After the appearance of Part 1, I was contacted by several ex-Sheffield students who had been to Rovinj in succeeding years. The Easter field course continued into at least the early 1970s. Len Hill told me in 2015 that they ended because in our time such courses were funded as part of the honours course by grants from local authorities to the individual student. Then funding was given direct to the universities to fund such activities. However, the funds disappeared into the maw of university administrations and funding for these field courses ceased.

Francis ETB. 1964. Rovinj, Easter 1964. 1964. University of Sheffield Gazette, Number 44, October 1944, 74-75.