This article arises from the previous one on the 1952 film, Strange Cargo. It concerns two women who were the subject of articles in the major news magazines and cinema newsreels of the day. They had kept crocodilians throughout the Second World War and beyond while leaving the unanswered questions of who they were and what happened next. One of the women, along with her alligators and crocodiles, appeared in Strange Cargo.

|

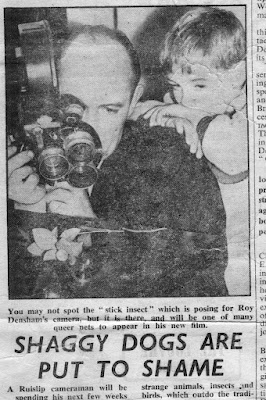

| This still photograph taken during the filming of Strange Cargo shows Pen Densham, 4, with 'William' the Chinese Alligator on the floor of 31 London Street, Chertsey, Surrey, in late 1951. |

The main story began with an article in Picture Post magazine of 10 January 1948 entitled, Alligators and Old Lace. The photographer was Charles ‘Slim’ Hewitt later renowned for his later work as a cinematographer on BBC television’s Tonight programme. The article began:

Miss Thelma Roberts and Miss Enid Davis in a life-long friendship, have acquired a very remarkable similarity of tastes. It isn't every day you meet two people whose idea of fun and friendship keeping alligators. Most folk, in fact, prefer dogs or cats. MIss Roberts and Miss Davis just can't understand that.

The articles gets a little confused about alligators and crocodiles but the women had a Chinese Alligator 5½ feet long and two Nile Crocodiles of 5 and 7 feet. The Chinese Alligator (‘William’) had been injured by a bomb during the London Blitz; it was said to be 11 years old. He had a galvanised iron ‘tin’ bath in the 10 foot square living room accessed by a wooden ramp. The smaller Nile Crocodile (‘Peggy’) was 8 years old and lived in a glass-sided tank also in the living room. The larger crocodile (‘Peter’ but said to be a female) was 22 years old and ‘once lived in a Madagascar temple’. That one was kept in a sturdy galvanised iron tank in the tiny kitchen because it fought the Chinese Alligator on sight and Thelma Roberts had once been bitten while trying to separate them.

Anybody who has kept reptiles will be asking the same question as the reporter. How could they have fed them throughout the war with meat rationed, as it still was in 1948. The answer was, ‘horsemeat, fish—either fresh or salt—crows and rooks, brought in by interested farmers in the neighbourhood’. The other obvious question is how were they kept warm? In one of the photographs thin electrical leads can be seen around the galvanized iron tank. Were they using the metal aquarium heaters used before the glass-tubed elements became available? If so, in a cold 1940s cottage, the electricity bills must have been high, even if kettles of hot water were also used by day and a fire kept in the grate.

The one-room wide cottage was 31 London Street, Chertsey, Surrey. It is clear from the article that the local council was ‘uneasy’ about the house being used ‘to offer its bounteous hospitality’ to the reptiles.

Picture Post was read by half the British population. This was a story, in 21st century terms, going viral. The USA’s Life magazine, read by around 13.5 million people, ran a shorter version of the article on 16 February 1948 with two of Hewitt’s photographs (all can be seen at Getty Images who appear to hold the copyright). The story was also carried by the magazine Pix in Australia on 28 February. Then, on 29 August 1949, British Pathé included a short clip about the women and their animals in a cinema newsreel. This time the women wished to be anonymous and the crocodilians were called different names. The clip can be seen here. What is striking throughout is how tame the alligator and crocodiles were when kept as domestic pets and handled frequently.

Then came Strange Cargo in 1952. By then Miss Roberts and Miss Davis were publicity shy and it took considerable persuasion (and the gift of a young crocodile) by Ray Densham to be allowed to make a film in the house, this time with only Thelma Roberts appearing. The Chinese Alligaor had also grown--to 6' 4".

Discussion on the Chertsey Society’s Facebook page in February and March 2021 on the ‘Alligator Ladies’ (since extracted as articles for local news magazines by Victor Spink) included neighbours recalling that ornaments on their mantelpiece shook when the crocs slapped the sides of their tanks with their tails. and that the ménage moved to Denmark House, Windsor Street, Chertsey where the animals were kept in an outbuilding. That must have been after Strange Cargo was made in 1952. The next owners of Denmark House retained the gardener employed by ‘The Alligator Ladies'. He reported that the ladies would come out and talk to him about the alligators being hired for films and television. The gardener asked Thelma Roberts, if Peter, the larger Nile Crocodile, had ever bitten the ladies. She replied, “No, he is very well behaved”. Then he saw marks on her arms. "But what about those marks on your arms, ma'am". "Oh well”, came the reply, "sometimes he forgets himself”.

The comments of the gardener on hiring the animals out for films and television would explain the Picture Post article’s wording, ‘Miss Davis, unlike her friend Miss Roberts, was never interested in alligators professionally’ which suggests that Thelma had some sort of job working with animals.

Armed with that knowledge, I realised that the British film, An Alligator Named Daisy, was released in 1955. A look at stills from the actual movie as well as for publicity shows that at least most of the shots were of a Chinese Alligator of the right size. Unfortunately there is no mention of who supplied the animals in any of the online sources, other than that a rubber model was used for some shots. My bet is that Thelma Roberts was, in modern terminology, the alligator wrangler and supplier, although some publicity stills with some of the stars may be of a larger American Alligator. However, others clearly show a Chinese Alligator of the right size, with Diana Dors, Donald Sinden and Ronald Culver, for example.

The names given to the beasts in Pathé News are possibly suggestive of some sort of röle in show business. One of the Nile Crocodiles was called 'Nitiqret' after the ancient Egyptian Princess, also known as 'Nitocris'. The Chinese Alligator had a name that sounded like 'Kelon'.

Before 1960—probably in 1959—Miss Roberts and Miss Davis left Chertsey. But despite extensive searches I have been completely unable to find any information on where they went or on what happened to them and their animals.

I have tried to glean clues on who they were from before their appearance in Picture Post in 1948. In July 1944 a photograph of Thelma smoking a cigarette with the alligator was published in the Royal Navy’s newspaper for the submarine service, Good Morning (the caption garbled her name).

|

| From Good Morning July 1944 |

In August 1941, the West London Observer (and other newspapers in England) carried the following snippet:

Tame Crocodile to Help Savings Drive

Do you want to shake hands with an alligator? Peter, 4½ feet crocodile, will be only be too pleased to oblige if you will purchase a War Savings Certificate. He is the pet of Miss Thelma Roberts, of Hammersmith, who came into possession of the animal shortly after war broke out. Although ten years old, with 78 teeth, Miss Robert has tamed and trained him, so that now be shakes hands with visitors and takes tit-bits from their fingers.

That event must be connected with a press photograph from 1941 (which can also be seen at Getty Images) showing Thelma Roberts with her alligator on a dog lead outside a London shop.

The only real clue I have on who the two women might have been has come from the recently released 1921 Census. I have found a Thelma F Roberts describing herself as: single, aged 26, Irish English, born in Hampton Hill (now in the London Borough of Richmond) and living in two rooms at 346 King Street, Hammersmith. Her occupation is shown as ‘dressmaker’. Also living there as her ‘assistant to dressmaker Miss Roberts’ was W. J. Davies (note the ‘e’ in Davies), aged 28 and born in Manchester. The 1929 electoral register shows Thelma Roberts and Winifred Davis (no ‘e’), along with two other women, living at that address. That Miss Davis was not at the address in 1931 but listed in the 1939 Register was a Winifred Margaret Davis (born October 1889; occupation ‘house keeper’). However, to add to the confusion, a change made later showed her name as Emily! Thelma Roberts is not shown at the address in King Street in 1939. Did the first reports get Miss Davis’s name of Enid wrong or, perhaps, was it was Winifred was known by? Whatever the reason it does seem possible or even probable that the Misses Roberts and Davis who lived in King Street, Hammersmith, were the ones who later moved to Chertsey. The ages given in 1921 certainly match their appearance in 1948 as women of 55 and 58.

Given such information from the 1921 census it is usually easy to find other information, like dates of birth and death. However, I have have found nothing at all. Similarly, other than the mention of Thelma Roberts coming into possession of the alligator shortly after the start of the war, there is no further information on where or how she obtained any of the crocodilians.

It does though seem that if we have the right Miss Roberts she had more strings to her bow than dressmaking. In 1931 there was an advertisement also in the West London Observer. Miss Thelma Roberts of 346 King Street, Hammersmith was offering piano lessons with ‘special attention to children and beginners; moderate fees’. Could she have acquired the animals, perhaps from a reservist called up for the war, with a view to hiring them out to entertainers and the film industry?

London bombing records show that a high explosive bomb fell approximately 100 metres from the house on King Street. Could this have been how the alligator was injured?

The title of the article in Picture Post is clearly a play on words from the Broadway production and popular film Arsenic and Old Lace which had two made murdering spinsters as main characters. In articles written about them, the ‘Alligator Ladies’ are referred to as spinsters and old friends. However, the only other clue I have been able to glean is that I can clearly see a wedding ring on Thelma’s finger. Had she been married or was she wearing the ring for some other purpose, as spinsters wishing to avoid male attention sometimes did? The clue, though, led nowhere.

None of this throws any light on what happened to the ‘Alligator Ladies’ after they moved from Chertsey. Does anybody out there know what happened next, or of, say, the adult animals eventually ending up in a zoo or private collection somewhere?

Pen Densham has again provided some of the photographs etc. from the family collection and from Strange Cargo.

|

| Pen Densham with young crocodile. I think this is the one given to Thelma Roberts by Ray Densham and possibly obtained from Charles Schiller who appears with two in the film. |