For my post on Burgess Barnett of 29 January 2014 I could not find a photograph of him. By chance I found one while looking through copies of Animal & Zoo Magazine (earlier Zoo & Animal Magazine) from the late 1930s. I have amended the original post. Here is the photograph from the July 1938 issue (volume 3, no 2):

Zoology has a discipline: evolution; zoology is vertically integrated, concerned with biological organisation at the level of organisms in their environment, organs, tissues, cells and molecules. This blog meanders through the animal kingdom, from aardvarks and anoles, through mouse and man, to zorillas and zebras.

Saturday, 28 February 2015

Friday, 27 February 2015

Introduced Wall Lizard Colonies in England: How Do They Survive?

Over the past hundred years or so, Wall Lizards (Podarcis muralis, formerly Lacerta muralis) that are native to many parts of continental Europe have been released deliberately or accidentally in southern Britain. Some have survived as colonies and some colonies have thrived, especially in the extreme south.

The usual explanation for why non-native oviparous reptiles do not survive in colder climes is that ground temperatures are insufficient for the embryos to develop and hatch either at all or before winter. Clearly, there are parts of England where Wall Lizards can breed and such lizards, the results of a ‘natural’ experiment, have been the subject of a very recent study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society.

The results are clear and show how Wall Lizards in England have adapted to colder conditions. The duration of incubation is reduced and the embryos are allowed to develop longer in the mother before oviposition (i.e. the mother gives the young a head start before subjecting them to a colder life in the egg). The mother can thermoregulate behaviourally even on relatively cold sunny days and bring the embryos to basking temperature. Hatching early, by an estimated two weeks, would allow the young to feed before hibernation and maintain a higher body temperature by behavioural thermoregulation.

That much seems clear. However, I am by no means convinced by the authors’ suggestion and thrust of their argument that the adaptive phenotypic shift they have recorded is the result of rapid selection (some of the colonies have only been in existence for a few decades). I am not convinced at this stage that their studies cannot be explained by physiological plasticity; in other words, that Wall Lizards can adapt to a wide range of external thermal conditions as a normal physiological response. The trigger to retain embryos for longer could be subtle, night-time body temperature for example, while the embryos/eggs could be programmed for early hatching by incorporating a chemical signal at the time of oviposition.

I would suggest that two key experiments need to be done. The first is that continental Wall Lizards be subjected to the conditions that obtain in southern England. The question then is: are the responses the same in the first year as in those lizards from introduced colonies? The second is the reverse: do introduced lizards kept in continental European conditions maintain the decreased incubation duration in the first year or not? If there has been a genetic adaptive shift, the effect should be maintained. Those and further longitudinal studies should enable the results of selection to be distinguished from the results of phenotypic plasticity, and by swapping eggs, to distinguish possible genetic from epigenetic effects.

Tuesday, 17 February 2015

Selfridge’s Aquarium: Who was Charles Schiller?

In my post of 11 February on the short-lived Selfridges Aquarium of the late 1930s, I noted that the designer of the equipment was Mr Charles Schiller. In looking through old copies of Aquarist and Pondkeeper (always known simply as the Aquarist) I had come across Mr Schiller’s name and so I began digging in order to learn more.

The aquatics trade, whether to provide the amateur fish keeper and breeder together with the ornamental aquarium trade or to supply public aquaria, has produced some highly entrepreneurial individuals over the past century. Some have been salesmen, some have been natural been natural showmen, some have been businessmen of ability—and some have been crooks.

Charles Schiller was an obviously accomplished salesman, showman and businessman and I have found that he was involved with the aquatics trade from the 1920s until the 1970s.

I managed to trace him because his business in the 1930s (Wigmore Tropical Fisheries Ltd) was in Jason Court off Wigmore Street in the West End of London. The 1935 Electoral Register shows him to be Paul William Charles de Zille Schiller living at 74 Wigmore Street, right next to Jason Court. He was born on 17 July 1906 in Hendon Registration District. In 1937 he married Joan Elsie Shephard (1914-1974) at Marylebone; they had three children between 1939 and 1944. Charles Schiller die on 24 January 1980 at Wycombe in Buckinghamshire.

In the 1930s Wigmore Tropical Fisheries was at the Jason Court address. These are advertisements from the Aquarist in 1934.

Then I discovered that Charles Schiller’s involvement with Selfridges did not begin in 1938 with the construction of the public aquarium in the roof garden. In the November-December 1935 issue of the Aquarist came the announcement:

It would appear that Charles Schiller had a flair for publicity as well as rich and royal clients. There are newspaper reports of his having been responsible for King George VI’s tropical aquarium at Buckingham Palace. Newspapers also reported some of his activities in importing fish (with the usual degree of journalistic licence). On 20 March 1935, the Western Morning News reported:

Sea-sickness is suspected to have been responsible for the death of three tropical fish of a collection numbering 500 which reached Plymouth last night in the liner Washington from New York

The fish had been brought from the Pacific and from the Panama Canal zone in specially-prepared tanks, which have been kept at a temperature ranging from 70deg. to 85deg. From the Canal the fish were conveyed by the sea route to New York, and there were placed on board the Washington.

The fish travelled to London in two warmed first-class carriages, and to maintain the temperature, the engine was attached half an hour before the train started for Paddington.

Mr. Charles Schiller, F.R.H.S., who has imported from all parts of the world, said the present collection had been brought for Mr. W. Woolland, of London, who made a hobby of collecting tiny fish. The specimens belonged to the Mollinesia [sic] class, and included a representative of the new Liberty “Molli” which had been caught in San Salvador, and was being introduced into Europe for the first time.

Mr. Schiller said the fish, which were only about an inch or two in length, had not been fed during the voyage from New York. This precaution, he explained, was taken because fish taken from their natural surroundings were liable to sea-sickness…

Was the Plymouth reporter being wound up or was getting a headline more important than accuracy?

Earlier, on 21 August 1933, the Aberdeen Press and Journal carried a story about Charles Schiller and his shop.

Few people know that London has a store of live jewels within three minutes of one of the busiest thoroughfares. Between two and three thousand of these microscopic bits of beauty wheel and dart and hover in electrically-heated tanks in Wigmore Street; specks of lovely colour, humming birds of the water—tropical fish!

…Two of them made history recently by being filmed for a peace propaganda picture. When they appear on screen they will look as large as sharks…

…”I began to collect such fishes,” Mr. Charles Schiller told me, “when I was twelve. A sea-captain relative brought me home two or three of the hardiest sort from a tropical swamp. I kept them warm by means of an oil stove and used to creep downstairs in the dead of night to see if they were warm enough and not too warm…”

I have also seen second-hand newspaper reports that Charles Schiller organised an expedition costing $15,000 to South America to collect Neon Tetras. The story of the discovery of the Neon Tetra and its early history in the aquarium trade is an interesting one. Early specimens changed hands for large amounts of money; in Britain £100-200 each, it was reported, or £12,000 in today’s money. I know nothing more of the Schiller expedition other than to point out that the cost today would be a quarter of a million pounds. Had somebody got an extra 0 or two from somewhere?

What happened to Charles Schiller and his business during the Second World War, I do not know. However, on 24 August 1949 the Singapore Free Press reported that Charles Schiller had imported seahorses to UK from Singapore under the first import licence granted since the war (major import restrictions were in place to the protect the £ sterling) for the Colonial Exhibition: ‘They were sent by Mr. Charles Schiller, a tropical fish engineer for the past 25 years’. Not surprisingly, having been sent by sea, only two out of thirty-six survived the journey. The Colonial Exhibition in London ran from 21 June to 20 July; a film of it can be seen here but the seahorses do not appear.

Wigmore Tropical Fisheries Ltd was wound up in 1950. The earliest copy of the Aquarist I have is July 1951 and in an article on a new sea-front aquarium at Southsea on the south coast is a photograph of Charles Schiller. Whether he was financially involved with this or other public aquaria I do not know. However, a new business, Aquarium Supplies Ltd, now at 16 Picton Place, a short distance from the original premises, was advertised in the same issue and contained the statement: ‘We have just completed the new Southsea Aquarium, which we designed and built in two months…’

|

| Charles Schiller (left) |

In February 1952, a full-page back cover advertisement in the Aquarist for Aquarium Supplies Ltd stated: "We specialize in the importation and distribution of the Harlequin fish (Rasbora heteromorpha) and can offer a large number of these fish in three sizes."

However, in the April 1953 edition of the Aquarist came the news that Queensborough Fisheries (owned by A. Rous) had acquired the shop at 16 Picton Place.

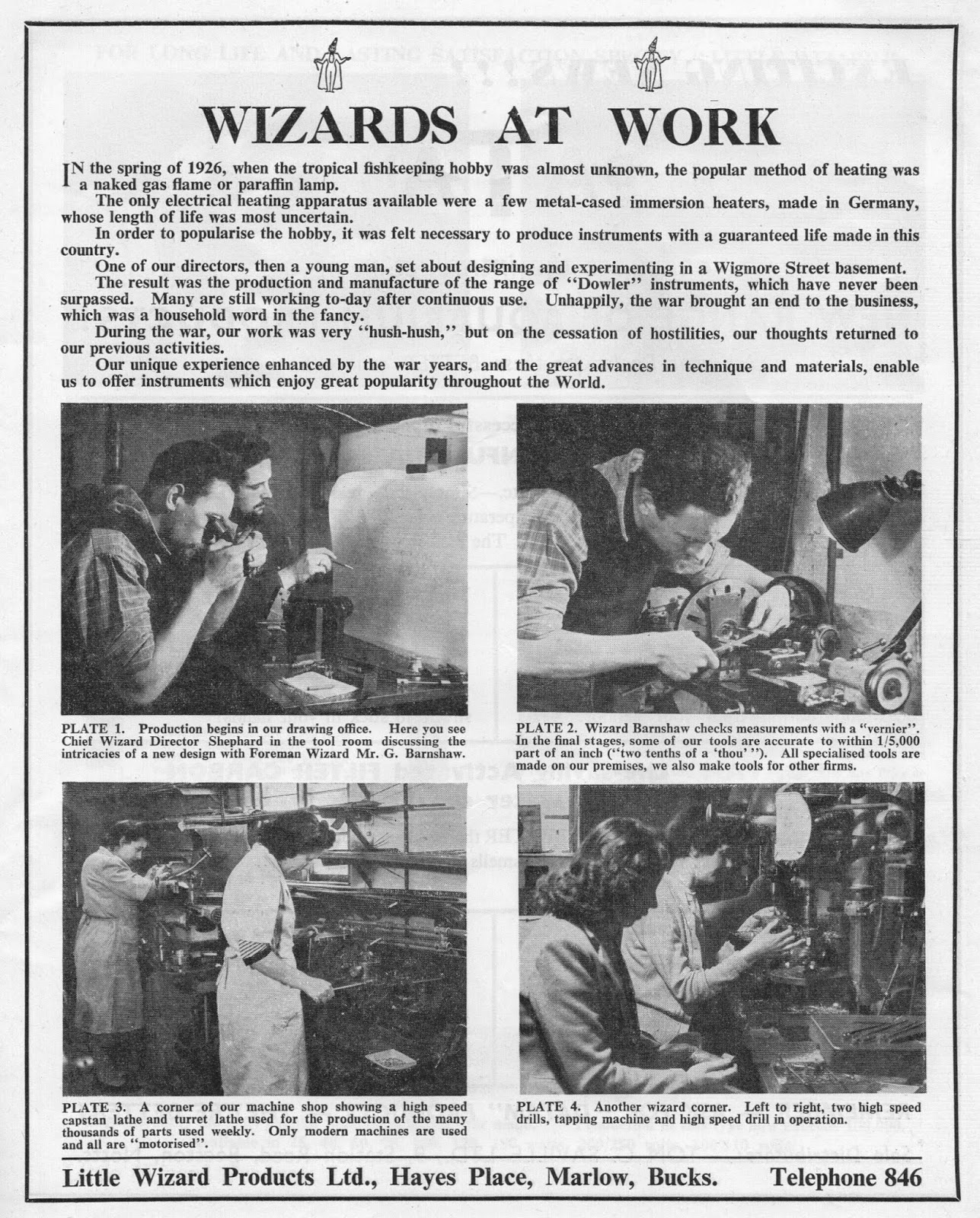

It became clear in the June 1953 issue that Charles Schiller had moved into the manufacture of aquarium heaters and thermostats with Little Wizard Products of Marlow, Buckinghamshire. Whether this was another venture he had been involved with for some time is not clear. However, there are clues. Aquarium Supplies Ltd (the company was dissolved in 1959) was shown as a service agent for Little Wizard products. In a three-page advertisement in the June issue it is stated: 'One of our directors, then a young man, set about designing and experimenting in a Wigmore Street basement. The result was the production and manufacture of the range of "Dowler" instruments, which have never been surpassed. Many are still working to-day after continuous use. Unhappily, the war brought an end to the business, which was a household word in the fancy. During the war, our work was very "hush-hush," but on the cessation of hostilities, out thoughts returned to our previous activities". There could be an additional family connection with this business. In the advertisement, a photograph is shown of "Chief Wizard Director Shephard in the tool room discussing the intricacies of the new design..." Shephard was the maiden name of Charles Schiller's wife.

However, in the April 1953 edition of the Aquarist came the news that Queensborough Fisheries (owned by A. Rous) had acquired the shop at 16 Picton Place.

It became clear in the June 1953 issue that Charles Schiller had moved into the manufacture of aquarium heaters and thermostats with Little Wizard Products of Marlow, Buckinghamshire. Whether this was another venture he had been involved with for some time is not clear. However, there are clues. Aquarium Supplies Ltd (the company was dissolved in 1959) was shown as a service agent for Little Wizard products. In a three-page advertisement in the June issue it is stated: 'One of our directors, then a young man, set about designing and experimenting in a Wigmore Street basement. The result was the production and manufacture of the range of "Dowler" instruments, which have never been surpassed. Many are still working to-day after continuous use. Unhappily, the war brought an end to the business, which was a household word in the fancy. During the war, our work was very "hush-hush," but on the cessation of hostilities, out thoughts returned to our previous activities". There could be an additional family connection with this business. In the advertisement, a photograph is shown of "Chief Wizard Director Shephard in the tool room discussing the intricacies of the new design..." Shephard was the maiden name of Charles Schiller's wife.

In the 1950s, the market for aquarium heaters and thermostats was very crowded. There was a multitude of manufacturers all claiming they were the best (there seem to have been even more in the 1930s when electrical heating was being developed).

In 1974, Charles Schiller wrote a letter to The Times from the Springfield Electrical Company Ltd in Marlow, Buckinghamshire. He complained that manufacturers of aquarium electrical equipment had not been given sufficient time to meet new regulations being imposed. He continued, ‘We seek only a reasonable period in which to meet the new regulations. We have no criticism of the new demands but if they are implemented on September 1 next, it will be necessary to lay off most of our workers. This will create a chain reaction involving the redundance of hundreds of workers, extending to many dependent on the aquatic industry. The writer can fairly claim to be one of the pioneers of the tropical aquatic hobby, which has developed since 1926, when we first started, into a £14m per annum industry, multiplied 20 times in the United States…’

It would appear that Little Wizard Products* somehow morphed into the Springfield Electrical Company. The former was dissolved in 1964 and the latter was incorporated in 1965 (and voluntarily dissolved in 1998). I vaguely remembered Springfleld heater-thermostats for aquaria. However, the only reference to them I could find was a heater-thermostat for sale on eBay.

That, at present, is all I know of Charles Schiller, one of a number of pioneers in the tropical fish trade in Britain, an activity that involved the whole spectrum of society, from the academic zoologist to the the clerk in the office and the worker in the factory. I will see if any other information emerges as I work through copies of the Aquarist. In the meantime, I would be pleased to receive any further information.

*Heaters made by British Aquarium Products, 'subsidiary to the Marlow Engineering Co', were advertised in the July 1946 issue of the Aquarist. All the companies mentioned must have morphed one into the other.

Thursday, 12 February 2015

Eric Thomas Brazil Francis (1900-1993). Zoologist

This story starts in the 1999 when Kraig Adler was looking for photographs to illustrate the biographies of herpetologists for his series, Contributions to the History of Herpetology. I told him that I had a distant shot of E.T.B. Francis but that the University of Sheffield was sure to have a portrait of him somewhere. Unfortunately, the university could not find one. Then, more recently and while looking for something else, I noticed that the Society for the Study of Reptiles and Amphibians had published in 2004 a reprint edition of ETBF’s book from 1934, The Anatomy of the Salamander with an introduction by James Hanken†. I also knew of but had not seen the dedication by the late Carl Gans to ETBF in volume 19 of Biology of the Reptilia published in 1998. When I did see that I realised I could add and correct some information to that gathered by Carl Gans from former colleagues. With all the volumes of Biology of the Reptilia now being online, I will not reproduce the dedication here. Jim Hanken kindly sent me a copy of his introduction to the reprint of The Anatomy of the Salamander which explains why ETBF is so highly thought of and why his book is still used today.

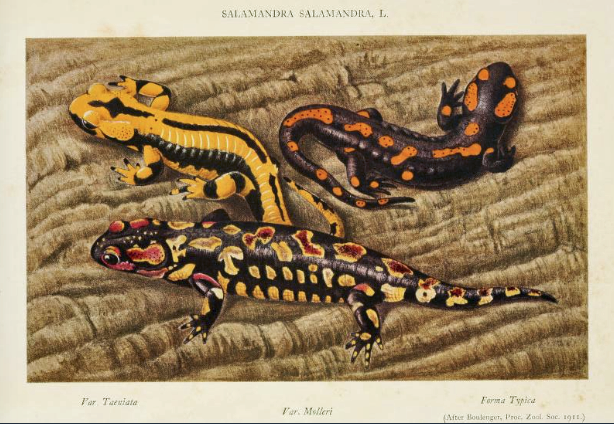

|

| The frontispiece to The Anatomy of the Salamander is from a paper by E.G. Boulenger. According to Hanken, the chromolithograph is by John Green |

ETBF loomed large in the life of zoology students at Sheffield. Our time there (1962-65) was at the crossover between classical zoology and what were then more modern approaches, so we still had to know vertebrates and many invertebrate groups backwards and inside out while getting to grips with comparative physiology, experimental biology, genetics and the like. Comparative endocrinology was the department’s major research activity, driven by Ian Chester Jones who had been appointed to the chair in 1958, and we were exposed to its influence from day one, with a lecture on the pituitary given, we discovered later, by Chester Jones wearing a sweater in need of darning and carpet slippers. A suitable culture shock was delivered to students accustomed to being taught by begowned grammar school teachers.

In our time at Sheffield, for the non-special part of Special Honours, the second and third years were combined for lectures. Thus ETBF gave his lectures on vertebrate zoology every second year, I think over two terms. As Gans picked up from the people he asked, ETBF was highly respected for his broad knowledge of the animal kingdom. That was the way then; university staff were expected to know a lot about a lot not just a lot about a tiny field. His knowledge of marine invertebrates emerged on a field course to the biological station at Rovinj in what was then Yugoslavia at Easter 1964. He was the man who knew what all the odd-looking things were we collected and where to find them in the dense German books that catalogued the fauna of the Adriatic. He was the man who also fixed students up with jobs in labs near their homes during the summer vacation; he knew lots of people throughout Britain and what they were doing.

Eric Thomas Brazil Francis was born on 3 August 1900 in Hackney in the East End of London, the son of Thomas Brazil Francis and Emile Anne Tourtel. At the 1901 Census, ETBF was seven months old and the family was living at 22 Bishop’s Road, Hackney, London. In 1912 this street in the east end of London was renamed Killowen Road; the house is a three-story terrace house. Thomas Brazil Francis, born in Peppard, Oxfordshire, was a pork butcher’s assistant. His mother, born in Peckham, London, was the daughter of Thomas J Tourtel, a printer’s reader and widower, born in Guernsey, who, with three sons and a daughter, also lived at 22 Bishop’s Road.

At the 1911 Census, the family lived in a very different environment. Thomas, Emilie, ETBF (age 10 and at school) and Emilie’s sister were living at Chalk House Farm, Great Kidmore End in Oxfordshire. Thomas was manager of a game farm (I presume a pheasant shoot).

Thomas Brazil Francis’s father was James Francis; he married Phillis Brazil in 1872 in Oxfordshire. James Francis is difficult to trace in the censuses since he was never present with his wife. However, there is a James Francis who fits the bill; he was a baker born in Kidmore End. Phillis Brazil was the daughter of Thomas Brazil (born about 1820) who, in 1881 was living about six miles from Kidmore End. He was a farmer employing three men and one boy; his wife was also called Phillis, and their daughter, by then Phillis Francis, and grandson, Thomas Brazil Francis, were also present on the night of the census.

Looking at the records, it is clear that the Brazils (originally, apparently, of Irish origin) were, over the years, butchers in London and the area of Oxfordshire north of Reading or farmers, also in that area north of Reading, over the county border in Berkshire.

In the 1921 Census Eric Francis, aged 21, was working as a fruit and poultrey farmer in the employment of his father, shown as Manager of a Game Farm and also as a fruit and poultry farmer. He graduated with an external London degree in 1929, suggesting that he was a late starter to university life. The University of Reading gained university status in 1926, indicating that he must have registered as a student before then but that once registered with the University of London, the degree he received was also a London one. His PhD, awarded in 1933, is a Readsing degree.

We know from his preface to The Anatomy of the Salamander written in August 1933 that he had worked in the laboratory of Professor F.J. Cole FRS (who wrote a remarkable historical introduction to ETBF’s monograph) at Reading. While there he prepared and donated specimens to Cole's museum. I have written about these here. In 1933 he was appointed assistant lecturer in Sheffield.

ETBF married Vera Christine Davison (born 26 September 1901) in 1938 in the Northumberland West Registration District. According to the 1911 Census, she was born in Hadley Wood, Enfield. However, at the census she was with her sister at her grandmother’s house, 8 Washington Terrace, Tynemouth which may account for why they were married in that part of England. Her grandmother, Annie E Ewart was a widow, aged 65, and a schoolmistress.

The Sheffield telephone directories from 1944 to 1983 show the Francis's address as 120 Brooklands Crescent, Sheffield 10.

Their son, Eric David Francis, was born in 1940. He was a classicist and his suicide in 1987 while employed by an American university must have been a great blow to ETBF and his wife, then aged 87 and 86.

At Sheffield, ETBF progressed from Lecturer to Reader in Vertebrate Zoology. Carl Gans stated that ETBF retired in 1973. However, this is wrong (see John Ebling's appreciation below). He retired in 1965 and I suspect 1973 was the year in which he gave up appearing in his old department.

ETBF died in 1993 in Sheffield, aged 93; Vera Christine Francis died aged 98 in 2000.

It would be easy to believe that ETBF was a dyed-in-the-wool comparative anatomist of the E.S. Goodrich kind. In that respect, The Anatomy of the Salamander probably counted against him; it was descriptive and descriptive zoology was out. His interests were actually wide and fully embraced experimental biology. Thus, in Scientific Research in British Universities 1960-61, his research activities are listed as:

- The conductive system of the vertebrate heart

- The salivary enzymes of amphibia

- Water relations in reptiles

- Host reactions to parasites with special reference to the gut

- Nutritional requirements of intestinal worms with special reference to larval stages

By the 1962-63 edition, the list had shortened to:

- The conductive system of the vertebrate heart

- Water relations in reptiles

- Host reactions to parasites with special reference to the gut

The work on the heart and on the salivary enzymes appears in the list of publication that accompanies Garl Gan’s dedication. I was well aware of his work on water relations in reptiles. As a new student walking along the zoology corridor to the large lab at the end, the offices/small labs were on the left. ETBF’s door was open (I never remember it closed) and he had a number of glass aquaria/vivaria on an iron stand on the right. In them could be seen a few reptiles; the most noticeable was a Stump-tailed Skink (Tiliqua rugosa). At some stage I learnt that he was measuring water losses across the skin and, once when I went to see him, he and his technician were actually doing so. All I can remember is that they were holding a small cylinder against the flank of a skink and saying they were not having much luck. He told me that he really wanted to look at cutaneous water losses in chamaeleons and needed some animals. I imported two species from Kenya during the 1964 summer vacation and he had about ten of them. I have been unable to find any reference to publication of his physiological work on reptiles. Earlier he had supervised work on rats in drift mines done by Graham Twigg, adding an ecological dimension to his interests.

I had, until I found the book online on research in British universities yesterday, forgotten that he also worked on the physiological effects of gut parasites on the host. I now remember, seeing in the animal house cages of mice (?) and somebody in a white lab coat telling me all about them. But I cannot remember who that was; it wasn’t ETBF, it wasn’t his technician who I think was called Martin. Was it a PhD student or an MSc student? I cannot find any reference to the work being published but it could have been, without ETBF as a co-author.

I can add a publication to the list given by Gans. ETBF was a contributor to A Dictionary of Birds* published in 1985, when he was 85. That volume was remarkable for the inaccuracy of some of the contributions on physiology but ETBF’s articles do not fall into that category!

Gans only knew ETBF in his later years but his correspondents noted that he had during his working life seen a transformation of the way university departments operate. Such change did not seem to suit him. At a student event, my now wife spoke to Mrs Francis for some time. The latter was apologetic and said that such occasions were much better for students in Professor [L.E.S.] Eastham’s days as head (1931-58) while the former received the strong impression that ETBF was unhappy with the direction in which universities, including Sheffield, and academic zoology were moving.

E.T.B. Francis was highly respected and remembered not only as a zoologist but as an Englsh gentleman.

-------------------------------

Note added:

I have found in the University of Sheffield Gazette this note marking Francis's retirement in 1965. It was written by F.J.G. (John) Ebling:

ERIC FRANCIS has devoted virtually the whole of his academic career to the University of Sheffield. Having obtained an external degree of the University of London in 1929, he spent four postgraduate years under G. F. COLE and N. B. EALES at the University of Reading, getting his Ph.D. in 1933. Subsequently, he was appointed Assistant Lecturer and Lecturer at Sheffield, being promoted to Senior Lecturer in 1946 and given the title of Reader in Vertebrate Zoology in 1954.

The pattern for the meticulous approach to his subject and to his life which Francis maintains, is to be found in his book, “The Anatomy of the Salamander", published in 1934. This work of nearly 400 pages contains 84 figures in 25 plates, nearly all drawn—very beautifully—by the author, an index of 21 pages, and 840 references, bearing an introductory note which reads: "All the works quoted in the bibliography have been personally examined except those marked with an asterisk”. Only 32 are so marked!

At Sheffield Eric Francis collaborated with the late FRANCIS DAVIES of Anatomy in a study of the conducting system of the heart of the salamander, and this was followed by a fine series of anatomical, histological and experimental studies of other vertebrate hearts by the two friends and other co-workers. In 1961 Francis returned again to the Amphibia with a paper on the function of the salivary secretions in frogs, toads, and—of course—the salamander; currently he is working on the water relations of reptiles.

The scope of his research does not reflect the whole range of his scientific interests. As well as his authoritative teaching of vertebrate zoology, he has maintained a flourishing research school in parasitology, a discipline we shall now lack. During the past two years, as early in his career, he has taken a most active part in departmental courses in Marine Zoology, appearing as at home among worms, molluscs and sea-anemones as among backboned animals, fully prepared to give a talk on sea-squirts at an hour's notice, and shaming his collaborators by his extensive knowledge of the marine plankton.

Francis, above all, is a scholar. As the pendulum swings between the view that research must be predominant and the counter pressure to turn universities into teaching factories, he suffers no dichotomy of inclination or duty; in his example scholarship grows by research and propagates through the teacher. Among his younger colleagues he is known for his unfailing friendship and courtesy, his great sense of humour and his unflagging zest for life. He is especially fond of music and is always to be found at chamber and symphony concerts; he has an insatiable interest in art and archaeology; he is a card-carrying cricket supporter; he enjoys good food and is an undefeatable traveller, who can reach any railway dining car in under four minutes from the gong while his fellow travellers have long before succumbed to languor in their compartments.

In the Department of Zoology his wisdom as well as his scholarship will be missed. This may well be the last manuscript over which a colleague will request his critical eye, and Francis will soon have written his last testimonials for Sheffield students and given them his last advice about choosing jobs. But he remains in his profession. During next session he will be a member of the teaching staff at Royal Holloway College, and he will continue to examine for the University of London. In wishing Eric and Christine Francis a happy future it would be premature to talk of retirement. More appropriate would be the comment of the captain of the Bios, the research vessel belonging to the Marine Station at Rovinj, Jugoslavia, which Francis recently visited in company with his colleagues and students. We had, on a beautiful spring day, put in to an uninhabited Adriatic island, and because there was no harbour it was necessary to jump from the bow of the ship on to the rocks. Francis performed this operation with a mechanical elegance which, perhaps especially in view of his personal statistics, drew universal admiration and the exclamation "E come un giovane, questo professore!"

F. J. G. EBLING.

-------------------------------

UPDATED: 8 August 2023 and 27 August 2025

†Hanken, J. 2002. Eric Thomas Brazil Francis and the evolutionary morphology of salamanders. Introduction to the reprint of E.T.B. Francis, The Anatomy of the Salamander, pp. v–xiv. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Ithaca, New York.

|

| The reprint edition 2002 |

*A Dictionary of Birds. 1985. Campbell B & Lack E (editors). Poyser.

Wednesday, 11 February 2015

Selfridges’ Aquarium: ‘One of the Sights of London’

I did not know that Selfridges, the Oxford Street store, once had a public aquarium. A Google search pulls up only one link—a reference in the Bartlett Society’s website to the existence of a guide book. I came across it in a short note in Water Life magazine of 13 September 1938:

Anybody who has visited the roof garden on Selfridge’s Stores, in Oxford-street, London, recently, will have seen the new building rising up there which will, when completed, house one of the finest aquariums in the country. There will be 26 tanks for cold-water fish, 30 for tropical and cold-water marine fish, and the remainder, about 130, will contain tropical fresh-water fishes. The tanks, which will vary in size, are to be arranged at a level which will enable spectators to see them with ease and comfort. One of the great features of this aquarium will be that no fish will be displayed in it which cannot be kept by the ordinary person at home.

The aquarium has been designed by Mr. A.D. Millar and Mr. Charles Schiller. The tanks and equipment are under construction to Mr Schiller’s design, by the Wigmore Tropical Fisheries, Ltd. Each of the tropical tanks will be equipped with a a Thermore thermostat and heater, so that they may be controlled individually…

Then the issue of 8 November 1938 reported: Selfridge’s Aquarium is Now Open:

Selfridge’s had a daily ‘advertorial’ column in The Times which described the aquarium in the purplest of prose. On 31 July 1939, the column contained the news:

Interesting specimens are continually being added to this unique collection and recently, when fishing off the South coast, one of our experts caught what looked in appearance to be a bunch of grapes. The local fishermen were quite unable to say what the cluster contained but our expert, believing it to be a group of piscatorial eggs, brought it back and placed it in one of our tanks. As a result seven octopuses have hatched out and, although it is early to prophesy that they will survive to maturity, they are at present thriving and growing well…

Interesting specimens are continually being added to this unique collection and recently, when fishing off the South coast, one of our experts caught what looked in appearance to be a bunch of grapes. The local fishermen were quite unable to say what the cluster contained but our expert, believing it to be a group of piscatorial eggs, brought it back and placed it in one of our tanks. As a result seven octopuses have hatched out and, although it is early to prophesy that they will survive to maturity, they are at present thriving and growing well…

Some of the inhabitants were described in The Times of 22 March 1939 including the Cow Fish, Lung Fish, Devil Fish (piranha) and now common but then highly sought-after recent introductions to the tropical fish trade, the Harlequin and the Neon Tetra. That article ended:

The Selfridge Aquarium…is open daily from 9 to 7 (Saturdays 9 to 1). The prices of admission are 6d* for adults and 3d for children under 12. We believe it to be the finest of its kind in Great Britain, and with no exaggeration can be designated “One of the sights of London.”

It also seems a bit underwhelming when considered nearly 80 years on. Even at the time it paled by comparison with the Zoo Aquarium. But public aquariums were popular and it could perhaps have been a useful reward to children having been dragged unwillingly around a department store or for somewhere a bored spouse to escape to in order to avoid the same fate.

The aquarium was shorted lived, which perhaps explains why it is so poorly remembered. I do not know how long the aquarium was kept open after the Second World War began but the roof gardens were closed in September 1940 because of bomb damage and stayed closed until 2011.

If ever the television series Mr Selfridge ever reaches 1938, we shall have to see if the aquarium appears as ‘one of the sights of London’.

*£1.40 today, adjusting for inflation.

Monday, 9 February 2015

Redstarts Again: Daurian in Hong Kong

Friday, 6 February 2015

Black Redstart Comes to Doonfoot in Ayrshire

The Ayrshire coast sometimes has a Black Redstart visiting during the winter. This year an immature male is living in a small area north of the mouth of the Doon around the gulley where Slaphouse Burn runs onto the beach. Hordes of twitchers and birdwatchers (not the same species) have been to see it just yards from the busy promenade that links Ayr and Doonfoot. Only dogs (the bane of seaside birdwatchers) seem to see it off for a while. It searches for food in the piles of seaweed and we have seen it taking insects from the air as they are disturbed.

I remember seeing a Black Redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros) on a bomb site in Fleet Street in London in the mid-1950s before I knew anything about birds or much else for that matter. It is difficult to contemplate that buildings destroyed by bombing had not been replaced by the 1950s but the sites became famous as the place to see Black Redstarts in Britain.

Yesterday my wife had the camera and the bird obliged us with these photographs.

I remember seeing a Black Redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros) on a bomb site in Fleet Street in London in the mid-1950s before I knew anything about birds or much else for that matter. It is difficult to contemplate that buildings destroyed by bombing had not been replaced by the 1950s but the sites became famous as the place to see Black Redstarts in Britain.

Yesterday my wife had the camera and the bird obliged us with these photographs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)