I know this sounds like a I’ve-danced-with-a-man, who’s-danced-with-a-girl, who’s-danced-with-the-Prince-of-Wales story but it actually illustrates how small the scientific world was in Britain in the years before the 1939-1945 War.

In my reading of the antarctic literature and the heroic attempt to obtain embryos of the Emperor Penguin (posts I made throughout 2014 on this site) by Edward Wilson, Henry Bowers and Apsley Cherry-Garrard in the Antarctic winter of 1911, I came across Cherry-Garrard’s run-in with Sidney Harmer, Keeper of Zoology at the Natural History Museum, or, in those days, the British Museum (Natural History).

|

| Wilson, Bowers and Cherry-Garrard after their return from the Emperor Penguin colony at Cape Crozier |

Cherry-Garrard’s animus to the Museum began when Cherry-Garrard delivered the penguins’ eggs to the Museum after Wilson and Bowers died with Scott on their return journey from the South Pole. Then in his book, In The Worst Journey in the World, he pulled no punches. His account begins:

Let us leave the Antarctic for a moment and conceive ourselves in the year 1913 in the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. I had written to say I would being the eggs at this time. Present, myself, C.-G., the sole survivor of the three, with First or Doorstep Custodian of the Sacred Eggs. I did not take a verbatim report of his welcome; but the spirit of it may be dramatized as follows:

FIRST CUSTODIAN. Who are you? What do you want? This ain’t an egg-shop…You’d best speak to Mt Brown: it’s him that varnishes the eggs.

I resort to Mr Brown, who ushers me into the presence of the Chief Custodian, a man of scientific aspect, with two manners: one, affably courteous, for a Person of Importance (I guess a Naturalist Rothschild at least) with whom he is conversing, and the other, extraordinarily offensive even for an official man of science, for myself…

Sara Wheeler in her biography of Cherry-Garrard, Cherry, describes how Harmer, Keeper of Zoology since 1909 and Director of the Museum since 1919—and now Sir Sidney—responded to the attacks on the Museum both to the press and to Cherry-Garrard himself. Harmer also pulled no punches: “the story seems devoid of any semblance to the truth”, and insisted that his staff had been maligned. George Bernard Shaw helped Cherry-Garrard with a series of letters (as he had with the book) and Harmer was left defending the impossible since Grace Scott, Captain Scott’s sister, had accompanied Cherry-Garrard on a subsequent visit to the BM, and confirmed in writing the attitude of the ‘custodians’.

Wheeler says the main culprit at the museum had died and I have not been able to identify him.

Arguments with Harmer had, however, begun earlier. Cherry-Garrard was invalided out of the army early in the 1914-18 War with ulcerative colitis and worked on his notes from the expedition. Those on the Adélie Penguin he submitted to Harmer (who was editing the reports from the Scott expedition) to see if they were publishable (according to him) or to be published (as can be inferred from Harmer’s reply). Harmer stated that the notes were not publishable as they stood. Wheeler says Cherry-Garrard, always fragile mentally as well as physically, exploded in a letter to Harmer and at the end of it raised his treatment at the hands of Harmer’s staff: “I handed over the Cape Crozier embryos, which nearly cost three men their lives, and has cost one man his health, to your museum personally, and . . . your representative never even said ‘thanks’.”

Between these spats, Cherry-Garrard supported Harmer over the slaughter of penguins for oil and meat in a letter to The Times (18 February 1918):

Sir,—May I back Dr. Harmer’s letter pointing out the danger of attacking penguin rookeries? If the slaughter of penguins and seals or the collection of penguin eggs is to be undertaken, the public should insist that it is done under the effective control of the Governments concerned, probably those of Australia and New Zealand. The true Antarctic penguins are fairly safe at present; there is no danger that the rookeries of the Emperor penguin will be harmed unless people want to go bird-nesting in 170deg. of frost; and the Adelie penguin is protected by the pack ice. But there is very great danger for the sub-Antarctic penguins which live in the islands north of the pack ice, and which are therefore more accessible…

Harmer it seems was a difficult man to fall out with. In his Obituary Notice for the Royal Society, W.T. Calman (1871-1952) noted:

…It is related that when the Trustees of the British Museum were considering the appointment of a Director, a very important person who was also a Cambridge man urged his appointment to the vacant post on the grounds that ‘Nobody could possibly quarrel with Harmer’.

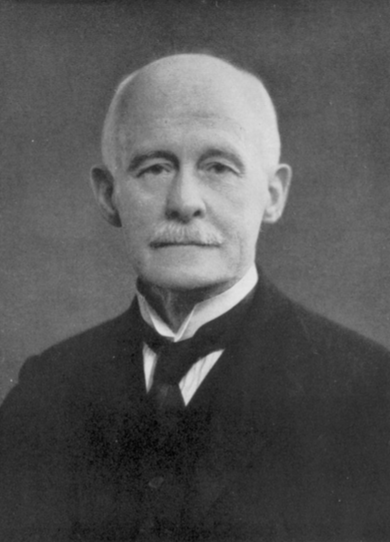

|

| Sir Sidney Harmer FRS |

Harmer is known for his role in the protection of whales in the southern oceans. Sidney Harmer was one of the old school zoologists who knew the entire Animal Kingdom while specialising in a particular group or groups. He was renowned for his work on what was then the Polyzoa but now often called the Bryozoa. At Cambridge he also became interested in whales, for example, a stranded Sowerby’s Beaked-whale on the Norfolk coast. When he moved to the BM he initiated the scheme under which stranded whales were reported to the Museum. According to his Obituary Notice, he did a great deal of work on whales which was never published and tried to sort out the classification of the dolphins.

His major contribution to the conservation of whales started in 1913. Calman wrote:

It is not clear when the Colonial Office first asked for help from the Museum in connexion with the whaling industry, if, indeed, they did ask for it. All that seems to be recorded is that in 1913 Harmer prepared a ‘Memorandum relating to whales and whaling’ which was printed on Colonial Office paper.

In order to mark whales to study their migration, Harmer supervised the first experiments with a large cross-bow to fire a marker into the body that could be recovered when, rather than if, the whale was killed and cut up by whalers:

At one time he had a large oil-cloth model whale behind the Museum and I seem to remember him in morning coat, striped trousers and bowler hat, excitedly watching the first shots…with this very barbarous-looking mediaeval weapon.

In short, Harmer became a first champion for whales. He analysed the statistics collected by the whaling companies and warned of the rapidly increasing rate of destruction of the whale populations around Antarctica.

To return to the first line of this post, I realised that I had met Sidney Harmer’s daughter, Iris Mary, and indeed that she was known by many of my former colleagues. At an event, I think to mark the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Institute of Animal Physiology at Babraham (since re-named as the Babraham Institute), Marthe Vogt, who had formally retired from the Institute in 1965 and would have then been 85, brought her former boss’s widow, Lady Gaddum, then aged 94. Shortly afterwards, incidentally, Marthe Vogt moved to live with her sister in California and lived until the age of 100 years and 1 day. Lady Gaddum, née Iris Mary Harmer, married Sir John Gaddum (Director of Babraham from 1958 until shortly before his death in 1965) in 1929.

I now find that Iris Mary Harmer had been involved in an important discovery. She was what would probably now be described as a clinical scientist after graduating with a first from Cambridge and then a London medical degree. She worked with Sir Thomas Lewis at University College, London on the famous ‘triple response’ and provided some of the first evidence, in papers published in 1926 and 1927, for the release of a histamine-like substance (Lewis’s H-substance) in human skin in response to minor injury. She died in 1992, aged 98.

So, there we have it, the very small world of British science in the early years of the 20th century. I talked with a woman—who was the daughter of a man—who upset an explorer—who collected Emperor penguin eggs on Scott’s final expedition. Much more interesting than to have danced-with-a-man, who’s-danced-with-a-girl, who’s-danced-with-the-Prince-of-Wales, don’t you know.