Major R. W. G. Hingston

|

| R.W.G. Hingston at a meeting of entomologists in 1923 |

In the first article of the first issue, under the title, Earth’s Highest Animals, Major R.W.G. Hingston described animals of the Himalayas. He had been naturalist and expedition doctor on the British Mount Everest Expedition in 1924, the one in which Mallory and Irvine disappeared in an attempt, possibly successful, on the summit. There is a short video of the expedition here.

Major Richard William George Hingston MC (1887-1966) served in the Indian Medical Service of the British Indian Army, the equivalent of the Royal Army Medical Corps in the British Army. During the First World War he was a medical officer in East Africa, France, Mesopotamia as well as on the north-west frontier of India. During the Second World War, long after his retirement from the Indian Army, he returned until retiring again in 1946.

During his time in India, and afterwards, he was a member of, or led, a number of expeditions and published accounts of his travels and collections as papers and books. He also did physiological studies on the effects of high altitude, adding to the knowledge that enabled later physiologists, notably Griffith Pugh, to get climbers to the summit during the 1953 Everest expedition.

On the Everest expedition he collected he collected 10,000 animals (mainly insects) and 500 plants; they are in the Natural History Museum in London.

His description of the high plateau brought to mind our standing on the Tibetan Plateau in Sichuan, China for the species involved were very similar, if not the same:

A friend in these high regions in the pretty little mouse-hare [an old name for pika]. About the size of a guinea-pig, they live like rabbits in a warren, honeycombing the ground not far from a stream with a complex network of tunnels. Living with them in constant companionship is a varied crowd of birds.

I found four kinds of mountain-finch, a horned lark, and a ground-chough [Ground Tit aka Hume’s Groundcreeper] sharing with the mouse-hares the same patch of ground as though they were one common family. The little birds hop around the mouths of the burrows; out pop the mouse-hares, skip about amongst them, while now and then a bird with pushing familiarity runs into the mouse-hare’s den.

More information on Hingston can be found here.

Fiction

Fictional stories, most of it in the Boy’s Own Paper style of animals performing feats of derring-do, appeared in every issue either as single short stories or as serials. I admit to never having heard of any of the 1930s writers but searches showed that they were British or American and, as far as I can see, were prolific authors of books and magazine articles often based on the great outdoors and its inhabitants. Some became well-known, for example, Henry Mortimer Batten (1888-1958). Batten is said to have spent time spent time in his twenties in the Northwest Territory of Canada as a prospector, forest ranger, surveyor and operator of motor boats. He then served in the French Army as a motor cyclist, being awarded the Croix de Guerre in 1915. Later, it is said, he served in the Royal Air Force. He was a prolific authors of books and articles, for adults as well as for children and teenagers. Batten became well known as an early BBC broadcaster. He also drove racing cars and when the Second World War came, served for a time as a despatch rider. He died in Canada in 1958.

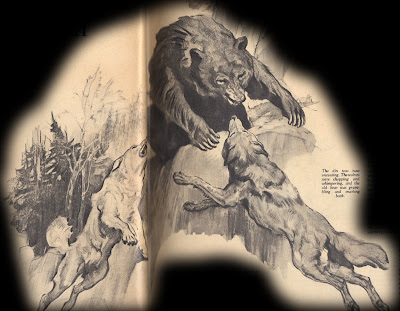

|

| A double-page illustration from H. Mortimer Batten's serial story Starlight the Wolf |

R P Russ, later known as Patrick O’Brian (1914-2000), became famous for his historical naval novels. Charles Thurley Stoneham (1895-1965) was a naturalist and big-game hunter as well as an author. Paul Annixter was the non-de-plume of Howard Allison Sturtzel (1894-1965), an American writer of children’s books and short stories. Elmer Ransom (born 1892) was also American. Apart from seeing their books in lists and booksellers’ websites, I have found nothing further on W. Gilhespy, Ernest Lewis or F.G. Turnbull.

No comments:

Post a Comment