On 15 May I posted a draft of this article. This version (9 June) for reasons explained below is a far more complete account.

The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals could not help me. Oldfield Thomas had named two species in honour of Smith in 1911: Smith’s Shrew, Chodsigoa smithii and Smith’s Zokor, Eospalax smithii, but nothing was known about Dr J.A.C. Smith, the Dr Smith so highly praised for his language skills and handling of difficult situations by Frank Kingdon Ward in On the Road to Tibet. The only clue I had was that in the website on Ward he is described as Jack Smith, a medical missionary. Thanks to the the genealogy sites findmypast.com and ancestry.com, British Newspaper Archive and Google searches, I have been able to find who our Dr Smith was and to bring together most of the varied strands of his life. When I had had nearly completed the first draft I found on the last page of a Google search a digest of articles from 2011 in the Spalding Guardian. That showed I was not the first person to research Smith. Margaret Johnson had written and published privately a book entitled The Life and Travels of Dr J.A.C. Smith. Smith was her late husband’s great-uncle.

I could no find trace of Mrs Johnson’s book in mainstream publishing. I then contacted the three outlets around mentioned in the newspaper article from 2011; they had no copies. I therefore wrote a letter to the editor of the Spalding Guardian, the publication of which brought me an offer of a book and a contact with her family. I am most grateful to Jane Cooke for sending me her copy and for telling me that Mrs Johnson, who she knew, had died.

Margaret Johnson’s book was beautifully produced and included not only the story of Smith’s life but some of his photographs as well as photographs of items he had sent or brought back to Spalding from China. One chapter in the book is devoted to Mrs Johnson’s three-week trip around China with her grandson in 2010 because:

Inspired and intrigued by Dr Jack’s account of his travels in China, I decided I would like to go and follow part of the journey myself…

|

The late Mrs Margaret Johnson at the

Terracotta Warriors in Xi'an in 2010 |

Margaret Johnson’s book, using family history and paperwork passed down from Jack Smith, together with assistance from the Baptist Missionary Society, filled in a number of gaps in my knowledge. I have also been able to follow up her work to fill in others.

John Arthur Creasey Smith was born on 18 May 1873 at Deeping St Nicholas, near Spalding in Lincolnshire to Robert Smith and Sarah, née Shepperson. Smith senior was a farmer; at the 1881 census he employed ’25 men and boys’.

Smith, on non-official papers, used Creasey Smith as a non-hyphenated double-barrelled surname, probably to distinguish himself from the thousands of John (Jack) Smiths in the country. The Baptist Missionary Society used Creasey Smith name in its reports, for example. The Creasey name was a tribute to the family’s governess Louisa Creasey (1850-1904); she had charge of the early education of the Smiths’ ten children.

Jack Smith was educated at the Albert Memorial College (now a public, i.e. independent private, school called Framlingham College) in Suffolk. That was the information given by the University of Edinburgh in its commemoration of those who served in the First World War. However, Margaret Johnson said that he went to a boarding school in Reading.

He certainly was in Reading working for a seedsman from 1890 to 1893. In the 1891 Census he is listed as ‘apprentice seedsman’ living in lodgings. He had helped on his father’s farm in 1888-89. Baptist Missionary Society records show that he had wanted to be a missionary from the age of ten. His father built a mission chapel built on his land in 1896 but his desire to become a missionary was reinforced while attending Kings Road Baptist Church in Reading where he heard a talk by a missionary based in Delhi. Early, while at home, he had been a Sunday school teacher.

|

Jack Smith, newly graduated from

Edinburgh

Photograph taken in Spalding

From Mrs Johnson's book |

In 1893 he matriculated at the University of Edinburgh to study medicine. In addition he was accepted as a student by the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society (still extant as EMMS International). Missionary Society students had their fees paid by the charity. His address in Edinburgh was 8 Hope Park Square in 1898; he also gave as his address that the Society and its hostel at 56 George Square. He graduated M.B. Ch.B. in 1898.

The Baptist Missionary Society provided Margaret Johnson with records of his enquiries and application for missionary work in 1898. Smith made it clear that he wished to work in a hospital where he could provide continuity of medical care, rather than in in an ‘itinerating’ rôle. He also made it clear he did not see himself as suited for a mainly evangelistic work or for work in the tropics. China was his preferred posting. He applied formally in February 1898. The Society issued a questionnaire to candidates which examined their christian knowledge and faith as well as their health. He gave the names of five referees: three were from the Baptists in Reading (a primary school in Reading is named after one of them, E.P. Collier), a Spalding clergyman, and the Superintendent of the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society. These are a few comments from his referees:

His habits are simple—his temper essentially unselfish—and his general deportment indicative of a steady plodding disposition which is his ruling characteristic.

Without exception the members of his family are persons of ability, power and practicality. The family is Christian and I need not add of indisputable respectability.

In a letter from one of his fellow students…the writer says’ “I doubt if there is a man amongst the final lists this year who nows his work in a more practical way than Jack: he may not be crammed up in all the high flown theories which in a written exam give men good places, but there’s not one of them more fitted to go straight forward and begin to practice—good old Jack”.

As to habits, temper, and general deportment I should say they are ‘Scotch’ in character, what more can a ‘southerner’ say or hope for in a friend! but he is good fellow to get on with.

He was accepted as a medical missionary on 26 September 1898. His acceptance was being watched by a missionary based in what is now Xi’an (later of terracotta warriors fame) on leave in Scotland. Moir Black Duncan wrote to the Baptist Missionary Society pointing out the shortage of shortage of medical missionaries in Shensi (Shaanxi) because of deaths and illness. Duncan wanted—and got—Smith appointed. Duncan had obtained a house in Xi’an for use as a hospital. At that time the hospital was treating 2000 patients a year.

Newspapers reported Smith’s departure to China as a missionary. Thus, the Reading Mercury of 25 February 1899:

A public meeting, organised in connection with the Baptist Missionary Society, was held in the King’s-road Chapel, Reading, on Thursday evening, the 16 inst., for the purpose of bidding farewell to Dr. J. A. Creasey Smith, who is leaving England on the 27th inst. to engage in missionary work in China. There was a large audience…

In China: The Boxer Rebellion

Smith emerges as having a key and controversial rôle in the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901. On 9 July 1900 45 missionaries, their wives and children were massacred in the governor of Shanxi’s compound in Taiyuan, the provincial capital. That massacre, present-day authors note, came to represent the enormity of the Boxer’s actions in the western world; thousands of Chinese were killed and many other Europeans in smaller numbers but Taiyuan was a defining event.

Press releases from the Baptist Missionary Society indicated that surviving missionaries were being evacuated to Shanghai and that on 2 August Mr & Mrs Moir Duncan and Dr. Creasey Smith were expected in ‘a day or two’.

Margaret Johnson suggests that Smith was in England in 1900 but the above report suggests he was caught up in the evacuation of surviving missionaries. She seems to have mistaken the year of the press reports on the evacuation.

Exactly one year after the massacre, Smith was one of two Baptists in a party of eight missionaries to re-enter Taiyuan at the invitation of the governor appointed by the new regime. An account from a diary on Wikipedia (full references there) of their arrival:

…The scene to-day was a strange contrast. Thirty miles off, outriders inquired as to the time of our arrival. Ten miles off, the Governor’s body guard blared out their welcome and unfurled their standards. Two miles nearer, the Shan-si mounted police made salute. Three miles from the city, we exchanged our litters for Pekin carts to facilitate our reception. A large and representative body of Christians seemed delighted to welcome us. Their faces bore clear traces of the sufferings endured. From this point the procession rapidly increased, as we proceeded between rows of officials, both military and civil. At the entrance to the pavilion stood an Imperial officer, who stepped forward and said, "I welcome you in the name of the Emperor of China."

The controversy arose over the details of the massacre in 1900 and identifying those who actually took part in the killings. There was, and still is, no doubt that the then Governor, Yu Hsien, was responsible.

Smith had commissioned a local evangelist named Zhao to go to Shanxi in autumn 1900 to gather information on the massacre from people believed to have been eye witnesses. But he also ensured the publication in a newspaper of an account of the massacre by a Yong Zheng, an aticle that was syndicated around the world. Having witnessed Yong Zheng’s baptism in 1899, Smith believed his version of events. However, the accounts of Zhao and Yong Zheng differed as to the detailed description of each murder and the direct involvement of Yu Hsien in the killings. However, historians tend to discount the account of Yong Zheng as being a just too detailed and well-remembered sequence of events of the massacre when recalled nine months later.

Smith was involved with other missionaries in the erection of memorial tablets at Taiyuan (Arthur de Carle’s Sowerby’s father, Arthur Sowerby, who had been based at Taiyuan and escaped the massacre because the family was on home leave, was present) as well as at other towns in Shanxi were missionaries had been killed.

In China: After the Boxer upheavals

Back in Shaanxi (Shensi) Smith could not avoid the ‘itineration’ he had been so keen to avoid before arriving in China, although extensive accounts of missionary activities indicate that he began to work up the hospital practice in Xi’an in 1904 . In 1902 he wrote from Siugan that he was ill and under strain from overwork. He had been there since November 1901 and ‘holding the fort’ alone except for a few days. He noted that of the thirty-eight months since he had arrived in China, ‘more than thirty had been spent quite alone, and the amount of personal responsibility upon my shoulders has sometimes been almost crushing’. He was asking for another medical missionary to be sent to join him.

An account of his medical ‘itinerations’ was published by the Baptist Missionary Society. It included the difficulties of transport, of being asked to treat incurable conditions, dealing with superstitious patients and noting the absence of hospitals other than those provided by the missions. Also included was a hefty lacing of religion for the readers at home who seemed more concerned with saving souls than saving lives. The following are extracts:

Imagine a springless cart drawn by a mule over an execrable track (one cannot dignify it by the name of road). We are seated, tailor fashion, with crossed legs, in this vehicle, and jolted and jogged, bumped and bruised, over thirty miles to San Yuan, our nearest station, to the north of the provincial capital. We are ferried across one river, wider than the Thames at London Bridge, and ford another, smaller, but much swifter. In the afternoon we reach our destination, thoroughly shaken and broiled. Mr. Madeley usually lives here, and it is pleasant to see him again after five months, and to have converse for a day or two, for we are both lonely bachelors, and live entirely alone.

Now imagine a small courtyard—40 feet long and 10 feet wide—a preaching hall at one end, a kitchen at the other. At the sides are living rooms. It is summer time, and Chinese summer too, stiflingly hot, no breeze; even should there be one, it would hardly enter this confined courtyard, for the overhanging roofs almost meet above one's head. As soon as it is light, patients begin to arrive, and the space is soon full, with crowds more around the door. The medicines and instruments being prepared in the preaching hall, the doctor begins to see patients, whilst Mr. Madeley, an evangelist, and several Christians read and speak in turn of the Holy One of God, the Great Physician, and whilst one is endeavouring to alleviate bodily and mental pain and suffering, one’s brethren-in-arms are trying to lead those waiting to the Healer of Souls, from whom they may obtain everlasting life.

Two years ago Mr. Morgan was to have moved to this place, but we had to flee. And now, who is to corne? Previously there were ten of us in this Shensi field, now there are but four, and this with a larger work and an ever-increasing cry of ‘Come over and help us!’ Who will corne? and who will help with all his power (of prayer and money) if he cannot come himself!

Several candidates for baptism were here preparing to go to the Annual Summer Church Assembly.

Home Leave 1903-04

In 1903-04 Jack Smith was on home leave (I cannot find any evidence that he was on home leave in both 1902 and 1904 as suggested by Margaret Johnson). Missionaries were clearly expected to spread the word while on leave and local newspapers recorded his appearances at Baptist churches at services or special meetings where he spoke of his experiences. Collections were made for the missionary society. He was at South Shields in September 1903 and Todmorden in Yorkshire for Sunday service and the annual missionary meeting in October. He had not come from China alone, as the Todmorden & District News of 23 October reported:

…Dr. Smith then proceeded to give a brief history of the Chinese boy who accompanied him. Nine years ago, he said, the lad lived in a little village not far away from Tai Yuen Fu, but sickness visited his home, and father and mother died. A kind doctor, Dr. Edwards—(applause)—took care of him. He attended Mr. Farthing’s (one of the martyrs) school until three years ago, when such terrible things happened. Dr. Edwards’s hospital was burned to the ground, Miss Edith Combs was burned alive, and it was realised that it was dangerous to allow the schoolboys to stay at Mr. Farthing’s any longer. They were sent to their homes, but this one had none to go to, for his relatives would not accept him. Two years ago the lad joined him that Pekin, and had been with him ever since, having travelled with him right across China. The reason he brought the lad to England was to arouse and increase the interest in foreign mission work all over the country.(Applause.)… Dr Creasey Smith afterwards exhibited maybe interesting Chinese curios. Both he and the Chinese lad wore national habiliments.—In point of interest it was the best missionary meeting held in Hebden-bridge for many years.

By November he had moved on to Faringdon, then in Berkshire, and it is the press report of this meeting that solved the question of his marriage. Both Margaret Johnson and I had come to the conclusion that he must have met his wife in China. She found that they were married in Ireland. However, there was another clue in the answers he gave in the Baptist Missionary Society’s questionnaire: ‘but circumstances prevent me from making any definite statements, at present, regarding marriage before going out’. Mrs Johnson knew from family records that his wife’s name was Annie Richardson Bailey. And who was a nurse at Faringdon Cottage Hospital (39 miles from Reading) at the 1901 Census? Annie Richardson Bailey. And who in his visit to Faringdon in November 1903 modelled a Chinese dress he had brought with him to the Baptist meeting? ‘Miss Bailey’. I suspect they had met while he was returning to stay in with church friends in Reading from medical school before he went to China in 1899, and that was the reason he was guarded in his intentions about marriage in his 1898 application to the missionary society.

He was in Bristol in February 1904 where he explained how medical services had ‘led to the spread of the Gospel’. He also said it was worthwhile returning to China and ‘told the pathetic story of martydom by a family of Christian natives, who in the late Boxer rising preferred death to denying their Saviour”. ‘He was’, he then said,’working in a province as large as England, and there were only two medical missionaries there; in the next province there was none at all, so altogether he had a parish as large as Great Britain to look after with twenty to twenty-five millions [sic] inhabitants’.

The baptists of Bratton in Wiltshire saw him in March 1904. He was in Spalding for his youngest sister’s wedding on 27 April. But then came his marriage to Miss Bailey on 18 May in the Belfast Registration District of Ireland. Annie Richardson Bailey was born on 5 September 1878, the daughter of William John Bailey and Margaret Ann Nicholson Bailey, at Lisburn in northern Ireland. Annie’s father (1848-1941) was a furniture dealer of 30 Bow Street, Lisburn.

Smith’s appearance in Chinese dress at missionary meetings in England really does seem to reflect what the foreigners at the missions wore from day to day. Margaret Johnson shows several photographs of missionaries thus attired. Perhaps it was done in order to ‘fit in’ and put their nervous patients and potential converts at ease. Today it would be condemned by some as ‘cultural appropriation’.

On 5th September there was a send-off meeting at a chapel in Islington as missionaries were returning to China, Doctor and Mrs. Smith amongst them.

1904-1908 and the end of missionary work

Smith was Britain again in 1906 but this time there is only one newspaper report of his presence at a Baptist event, this one near his base at Spalding: the South Lincolnshire Baptist Sunday School Teachers’ Conference in July. Shipping records show he travelled on the Empress of Canada from Hong Kong to Vancouver (he arrived there on 3 January 1906) and crossed the U.S.A. and then the Atlantic in the S.S. Lucania to Liverpool.

Shipping records show that he travelled to Canada on Canadian Pacific’s R.M.S. Empress of Britain. The Montreal Gazette of 26 July noted that on 18 July Smith had proposed a unanimous resolution of the second-class passengers thanking the members of the crew responsible for the service they had received while on board. I have not been able to find whether he crossed Canada and continued to China or if was visiting Canada and then returned to Britain. His wife did not accompany him on this home visit, presumably staying with the mission.

I also do not know when he and Annie arrived in Britain in time for them to leave Liverpool for Canada in 1907.

One directory of missionaries in China shows that Smith left the mission in 1905; that date is confirmed by a memorial volume on one of his colleagues, Stanley Jenkins. So he must have been back in England in 1906 because of ill health. However, his final severance from the missionary society only came in 1908. In view of his plans to move to Canada in 1907 that seems the most reasonable explanation for the discrepancy in dates. He had decided by 1907 that return to the missionary life was impossible.

R. Fletcher Moorshead, the Medical Secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society, in his review of the medical work of the society, Heal the Sick (London: Carey Press, 1929) wrote:

The summer of 1908 witnessed a number of reinforcements for the medical mission staff which were more than welcome as it was also a time of enforced retirements on account of ill-health. Dr. Creasey Smith, the medical pioneer of the Shensi medical mission, was obliged to relinquish the prospect of further mission work through that cause.

It is not easy to appreciate the vast effort and organisation that went into missionary work from Britain, the U.S.A. and some European countries and only on reading such reports could I get any appreciation of the scale of proselytization, social work, education and medical aid going on, all supported by large amounts of money raised by huge voluntary organisations back home. After reading it all, I am left with a feeling of both horror at the concept of promoting any religion, let alone with such fervour, and admiration for the genuine good that the education and medical aid did. We should also not forget the very high death rate from disease of the missionaries, as even a rapid look through the book on Stanley Jenkins shows. It seems that typhus was the major cause of death.

Canada

Jack and Annie, aged 34 and 29, sailed on 18 September 1907 from Liverpool on board the Allan Lines ship Carthaginian. They landed at Halifax, Nova Scotia bound for the town of Peachland in British Columbia. There, Margaret Johnson shows a receipt for $200 as initial payment on a Lot 7-2538 dated 25 October 1907 and another for $500 for the first payment on a different lot, 015-2538 from 4 December. Peachland was then a new town on the shores of Okanagan Lake and thought to be ideal for fruit growing.

Mrs Johnson indicates that the Smiths intended to settle in Peachland. Were they perhaps intent on setting up in practice with Jack as the doctor and Annie the nurse? Whatever, Mrs Johnson wrote: ‘For some reason, Jack and Annie spent barely two years in Canada’. I have been unable to find any information for this period in their lives and the episode leaves questions unanswered. Did they complete the payment on their lot or lots and did they build a house, for example?

Jack and Annie were not the only Smiths in Peachland. Jack’s cousin, Edward Freeman Smith, lived there; he was a beneficiary named in Jack’s will. Was he the owner of one of the plots Jack made an initial payment for in 1907? I have every reason to believe Edward Freeman Smith was born on 26 September 1883 at Deeping St Nicholas and died on Vancouver Island on 17 May 1968; he was a farmer.

China Again and Two Expeditions

The Smiths, after Canada, appear to have been based in Shanghai from around 1909. Jack then took part in two arduous expeditions within and beyond China. The question that has to be asked is how he managed that after having to quit as a medical missionary because of ill health.

The first expedition which began in 1909 and part of the Duke of Bedford’s Exploration, was the reason I became interested in Dr Smith and his eponymous mammals. He, the leader Malcolm Playfair Anderson, and Frank Kingdon Ward were those taking part. He was listed as assistant to Anderson when the Exploration ended in 1911.

|

| From Mrs Johnson's book |

My guess is that Smith replaced Sowerby for what turned out to be the last part of the Exploration, on the recommendation of Sowerby. As i wrote above, the Sowerby’s father was a Baptist missionary who had met Smith. Sowerby junior was born in Taiyuan.

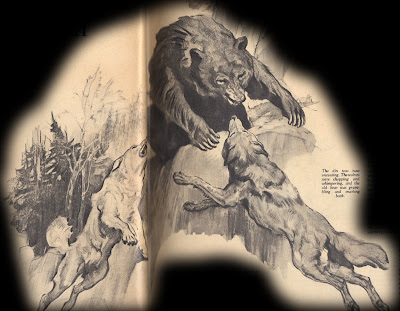

Then, in 1911-12, he was hired by George Fenwick-Owen (1882-1971) for a hunting and collecting trip in China. An account of that expedition was written by Fenwick-Owen's companion for the trip, the big-game hunter Harold Frank Wallace (1881-1962). They ran into difficulties as the violent upheavals that led to the fall of the Qing Dynasty began. To avoid the conflicts the expedition made its way in considerable discomfort across the Gobi desert to Russia.

|

Crossing the Gobi Desert

From Mrs Johnson's book |

I will not go into these expeditions further here but having more information will write about them later.

There is evidence that Smith was still spending time in Xi’an. He wrote an appreciation of his fellow medical missionary Stanley Jenkins who had travelled to China with the Smiths in 1904. In it stated that after their first year together, ‘I have made frequent and extended visits to S-an-fu [Xi’an], often staying with him for months at a time, and so speak from experience and observation’. Smith rushed from Hangkow (Hankou), 500 miles away, when summoned by telegraph to Jenkins’s deathbed, having left him a few days earlier in apparent health because, ‘I was obliged to return to Hankow’. But what was Smith doing during these years. Did he have some sort of medical practice? Was he ‘itinerating’? Or was he being paid by the wealthy Oldfield Thomas as one of his private collectors sending specimens to the Natural History Museum in London after the Duke of Bedford's sponsoship ended?

Harold Wallace in book describing his expedition wrote highly of Smith and gave his address in Shanghai:

Much of the success of our trip was due to the assistance of Dr. J. A. C. Smith, 320, Avenue Paul Brunat, Shanghai, and those who contemplate following in our footsteps cannot do better than secure his services. Talking the language like a native, he understands the Chinese thoroughly, and has a complete knowledge of skinning and preserving both large and small mammals and birds. I must express my indebtedness to him for much of the information I obtained. Had it not been for his knowledge of the natives and his skill in translating I should have remained in ignorance concerning many interesting points.

Avenue Paul Brunat, incidentally, was in the French Concession. It is now a section of Huai Hai Lu.

Smith was still in China in 1915 because on 9 May he wrote from Yen-an Fu (Yan’an) to George Ernest “Chinese” Morrison (1862-1920), then political adviser to the Chinese Republic and former correspondent of The Times, on the continued production of opium in Shaanxi. The editor of Morrison’s letter notes that Smith was one of Morrison’s regular sources of information.

Dear Dr. Morrison,

I do not doubt you are a busy man these days when so much advice is needed. Still I know you are intensely interested in what is happening in the interior of this country as well, and possibly a line on Opium may not be out of place…

Opium growing was almost entirely abolished in this province of Shensi last year, and in the autumn, when it is sown in the Southern and more fertile part of the province, strict proclamations were issued forbidding its growth. In late February and early March, however, the people were given to understand (not by proclamation, but secretly) that they might grow it as freely as they liked, a heavy tax to be levied on the acreage. I personally met two deputies sent by Lu Chien Chang the Chiang Chun, to see Mr. Shorrock the Senior English Missionary at Sianfu, to ask him to be silent about this matter and not report it to Minister or Consul, as Lu said he must do it to raise funds to pay his troops. Mr. Shorrock refused to make any promise of any nature regarding the matter - Spring sown poppy was now largely put in the ground and I personally have seen many thousands of mou of land growing it during this last few days.

About the 1st of May, new proclamations were issued threatening the direst penalties on all who grow it and ordering the instant plowing up of all sown. This after I had seen in the P[eking] & T[ientsin] Times a note of the impeachment of the Governor Lu of this province, for allowing its growth. The opium is still growing however and is being cultivated, the plants separated etc. This is not secretly, but openly done alongside the big main roads. This is evidently by orders of the Provincial Government for each Hsien or small town has its Opium Suppression Bureau, with soldiers and officials in abundance at their offices, many of them smoking the drug themselves, yet the opium grows within bowshot of the offices.Lu Chien Chang is a very heavy smoker himself, he is reputed to consume 2 ozs daily. He certainly accepted a gift of 20,000 ozs from Chang Yiin San, Shensi’s Brigadier-General and Ko lao hwei leader, when he arrived in Sianfu a year ago. Yesterday, in this city of Yen an fu, men were paraded on the streets with paper notices stuck on their backs and carrying gongs which they were beating, and accompanied by soldiers, a punishment for selling opium in small quantities - whilst well-to-do shop-keepers were heavily fined. Yet within 100 yards of the city wall opium is growing in abundance…

First World War

The University of Edinburgh’s memorial rolls show that from October 1916 until September 1917, Smith was with the Balkan Convoy, Ambulance of the French Red Cross, British Section (information on its formation and rôle here). He is shown, with Creasey spelt ‘Creasy’ as a Medical Officer in the Register of Overseas Volunteers of the British Red Cross.

After that voluntary service, he was appointed to the Royal Army Medical Corps, the appointment to begin on arrival in France—which turned out to be 22 October 1917. He served as a medical officer at a hospital at Noyelles-sur-Mer set up to treat the Chinese Labour Corps, non-combatants recruited in China doing essential work to support the armies in the field. Arthur de Carle Sowerby served as an officer in the headquarters of the Corps. Smith was promoted Captain in October 1918 just before the war ended. After the Armistice in November 1918, the Corps continued its work to clear the battlefields. Then, during 1919 and 1920, all 96,000 remaining in France were shipped back to China. Illness, including the flu epidemic took its toll; 900 graves are at Noyelles, with others elsewhere.

Jack Smith travelled back to China with the Labour Corps. It would seem that he completed the job in Hong Kong in June 1920, for there, Mrs Johnson shows a receipt from the army medical stores for instruments returned by Smith including ‘Forceps, Dressing 3’ and ‘Probe, 1’. He stayed in Hong Kong for a month (from 30 June, the day he returned the stores, until 20 July) at the Carlton Hotel for which he was charged 90 Hong Kong dollars. I do not know if he had been in Shanghai before Hong Kong but shipping records show he sailed from Hong Kong on the Empress of Canada and arrived in Vancouver on 9 August. There he visited his cousin, Edward Freeman Smith in Peachland, and then travelled across Canada to leave Quebec for Liverpool on board Canadian Pacific’s Prinz Friedrich Wilhelm (surrendered by Germany; later Cunard’s Empress of India). His ‘intended future residence’ on arrival at Liverpool on 31 August 1920 was ticked as a ‘foreign country’.

Annie Smith is shown as arriving in New York from Liverpool en route to Shanghai on 24 January 1920. In view of later developments it is interesting that she showed as her contact in the passenger list her father, W.J. Bailey of Bow Street, Lisburn, and not her husband, Jack. She can then be found arriving on board the Japanese ship, Arabia Maru, at Victoria, British Columbia, Canada on 18 August 1920, probably in time to overlap with Jack Smith’s stay with his cousin at Peachland. However, she did not accompany him on the ship to England.

In passenger lists, Jack Smith always gave his address in England as Selby House, High Street, Spalding. The ‘Misses Smith’ were shown as living there is Kelly’s Directory for 1919; they were his sisters, Helen and Annie.

Ship’s Doctor

Then Smith’s life took a different turn. He became a ship’s doctor and thanks to the records of merchant seamen’s tickets we have fairly detailed account of his voyages as well as a photograph from those records.

Smith worked for the New Zealand Shipping Company on board six ships (Paparoa, Ruahine, Wiltshire, Rimutaka, Suffolk and Hororata) between November 1920 and 1926. They were either refrigerated transport ships with passenger accommodation or just passenger ships, all travelling between New Zealand and Britain via the Panama Canal. The company insisted that its ships call at Pitcairn to relieve the monotony of the Pacific passage. Visiting ships brought relief to the inhabitants of that island. Smith, the ship’s doctor, was probably needed on Pitcairn on occasion.

Divorce

Smith divorced his wife in 1924; the decree absolute came on 9 February 1925. Margaret Johnson found a press cutting in a local Spalding newspaper describing the graphic details. A similar report was in the Nottingham Evening Post of 30 July 1924. Smith named Frederick John Wetherstone-Melville as co-respondent.

Thanks to the Wetherstone-Melville family (see below) who contacted me after the first version of this article appeared, I now know much more about what happened in Shanghai. A number of gaping holes and loose ends in the story of what happened to Annie after the divorce have been cleared up.

Fred Wetherstone-Melville had an interesting early but sad personal life. His date of birth was during the second quarter of 1885 (he was christened on 21 July) in Maidstone, Kent. While working as a ‘Draper’s Shopman’ he enlisted at Deal in Kent in the Royal Marines on 12 January 1901; on his records his date of birth is shown as 12 January 1883 which is clearly incorrect. My guess is that he pretended to be 18 in order to enlist. He served first in the Plymouth Division, then on board the pre-dreadnought battleship, H.M.S. Empress of India, then ashore in the Royal Marine Light Infantry Chatham Division and finally on the cruiser, H.M.S. Astraea. His character and ability were judged to be ‘Very Good’ throughout. He was discharged by purchase on 30 April 1906 and his address was given as ‘Health Department, Shanghai’. Astraea had arrived on the China Station in 1906 and my guess is that he bought his discharge in order to join the Health Department of the Municipal Council of the international settlement in Shanghai.

|

Frederick Wetherstone Melville in the uniform

of the Shanghai Volunteer Force |

The Health Department sent its inspectors for training in U.K. They had much to do in the prevention of disease and by all accounts achieved much in making Shanghai a healthier place to live. Wetherstone-Melville clearly rose in the ranks of the department and Shanghai society; in 1912 he was Master of the masonic lodge. He also served as a Captain in the Shanghai Volunteer Force where his training and experience as a private soldier in the Royal Marines must have proved useful. On his first marriage, to Alice Sophia Farrow (‘lately arrived from England’) on 31 January 1910, at the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Shanghai, his colleagues presented him with a silver jug. At her marriage Alice was shown as 37 and Frederick as 24. From the marriage records we can identify Alice as having been born in late 1872 in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. Her father was George, a sergeant in the 12th Regiment of Foot or East Suffolk Regiment. In 1891 she was a domestic servant and in 1901 was a nurse working in London. No unequivocal record exists for what happened to Alice. She was alive in 1912 since the Wetherstone-Melvilles arrived back in Shanghai on Norddeutscher Lloyd’s S/S

Princess Alice. Given the apparent reluctance of registrars to deal with double-barrelled surnames and the absence of a death record in Shanghai, it is possible that her death is listed as Melville and, indeed, there is listed the death of an Alice Sophia Melville of the right age in Reading, Berkshire, in 1915.

|

| Wetherstone-Melville in his carriage in Shanghai |

Wetherstone-Melville next married Ada Blanche Hill on 29 May 1917 in Shanghai. She had a son in England in 1920 and travelled back to Shanghai with the 4-month old from London on 26 February 1921 on board Glen Line’s S/S Gleniffer. That marriage did not last. Wetherstone-Melville obtained a divorce on the grounds of her adultery. Although he was given custody of the young son it was on condition that he lived in England where the mother had returned. He was unable to do this, and the child, then two, remained with his mother who never told the boy that he had a father who then lived in Canada. Only on joining the Life Guards at the age of 17 did he get to know about his father.

It was around this time, 1923, as explained above that Annie broke up with Smith and travelled back to U.K. with Wetherstone-Melville. Shipping records match the report in the newspapers. Wetherstone-Melville described as Chief Health Inspector for Shanghai Municipal Council, and Annie Smith, ‘Trained Nurse’, left Shanghai in April 1923 on the American President Lines ship President Pierce bound for San Francisco where they arrived on 3 May en route to England. The White Star Line’s Baltic brought them from New York to Liverpool where they landed on 4 June.

On 20 October they left Southampton for Shanghai on S.S President Arthur bound for New York, where a handwritten note was added on the passenger list to show they were to stay at the Belmont Hotel (since demolished but once the tallest hotel in the world). Wetherstone-Melville was shown as having a diplomatic visa for the U.S.A. Annie stated as a relative her sister, Mrs W.H. Powley of 62 Durley Road, Stamford Hill in North London..

Annie and Wetherstone-Melville were married in Shanghai on 9 April 1925. Her name appeared as Annie Richardson Creassy-Smith [sic] in the announcement in the London and China Express of 21 May 1925.

The Wetherstone-Melvilles did not stay in Shanghai for long. They sailed from Hong Kong in 1926 and landed as immigrants in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. He died in 1950, in Victoria. Shipping records show that Annie, by then a naturalized Canadian, entered the U.S.A. in a ship at Tacoma on 22 March 1951. She was travelling first class on the Holland-America Line’s cargo-passenger ship Dalerdijk’s voyage from Vancouver to Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Thanks to the daughter and son-in-law of ‘Shanghai Fred’s’ son from his second marriage we now know what happened to Annie, and have a photograph of her. Sometime after Fred’s death she moved back to Northern Ireland where she died on 23 September 1968, aged 90. She left part of her estate to the step-son she had never met. Fred, in his relatively short life, had obviously come a long way from the ‘draper’s shopman’ who enlisted in the Royal Marines.

|

Annie and Fred Wetherstone-Melville

in Vancouver |

We know little of Annie’s life in China, the nurse in the cottage hospital at Faringdon and the assistant matron of a hospital in Shanghai. She was listed as a member of the medical mission at Xi’an after her marriage in 1904. As Margaret Johnson noted: ‘Life cannot have been easy for Annie Smith during their marriage, with Jack constantly travelling…’. We do though know, from the details provided for U.S. immigration in the passenger lists that she was 5’ 5” in height, of fresh complexion with brown hair and blue eyes. She was a shown as a Quaker (Society of Friends) as were her parents in the 1911 Census.

I have tried—and failed—to find anything on Annie’s life in Shanghai or the hospital at which she worked. The only clue of an association with the medical profession is her entering the name of a doctor as her ‘friend’ on her voyage from Shanghai in 1923. He was Dr A.G. Parrott of 31 North Szechuan Road, Shanghai. A. George Parrott had an interesting history. He died on 22 May 1923 aged 67, only a month after Annie’s departure. His obituary in the British Medical Journal shows that he was a missionary who returned to London with his first wife and young family to become a medical student. After six years at the London Hospital he returned to China as a medical missionary. His first wife died in North China and as a result of the Boxer Rebellion he set himself up in private practice in Shanghai while engaging in all sorts of mission work. He was visiting physician to the Shantung Road Hospital for Chinese (still in existence under a different name). Was that where Annie was assistant matron?

New Zealand

|

Jack Smith in his uniform as a ship's

doctor. Note the First World War medal

ribbons.

From Mrs Johnson's book |

Margaret Johnson suggests that Smith moved to Wellington, New Zealand as a permanent base while he was working for the shipping line. However, this may have been after he had stopped travelling as a ship’s doctor. On his final trip to Spalding from Wellington in 1928 as a passenger on the Shaw, Savill and Albion’s line, Arawa, which arrived in London on 20 April 1928, he showed his intended country of residence as England. However, when he departed on 29 June on the New Zealand Shipping Company’s Ruapehu from Southampton to return to Wellington, he is shown with New Zealand as his intended country of permanent residence.

The press report on Margaret Johnson’s book states that Smith was never mentioned in the family because of his divorce—very difficult for those younger than 60 to believe but absolutely true for the decades up to the 1970s. In the English middle and working classes, divorce just did not happen to ‘respectable’ people. Such a matter would not be spoken of out loud but teacups would have rattled with the whispered gossip about the family in the towns and villages of south Lincolnshire. Poor Smith. He was better off at sea and in New Zealand.

Jack Smith died on 4 May 1929, aged 55, of a cerebral haemorrhage, at 135 Hataitai Road, Wellington, New Zealand on 4 May 1929. His grave is in the Karori Cemetery, Wellington. Mrs Johnson found an obituary in a local newspaper:

Dr J Smith, who for many years travelled as a medical officer on board the New Zealand shipping company’s steamers between England and the Dominion, and who was thus well known to thousands of New Zealanders, died at Haitaitai on Saturday. He was specially noted for his devotion to children on his many voyages. He was a native of Spalding, Lincolnshire and was 57 years of age [he was actually 55, two weeks short of his 56th birthday], being a school mate of Rev D.C. Bates of this city [Wellington]. For many years he was a medical missionary in China until his health broke down. The funeral was held yesterday morning, the service at the graveside at Karori being conducted by Rev. Cannon Sykes and Rev. D.C. Bates.

His will was granted probate in England. He left £6411 19s. 11d. The beneficiaries were two cousins (one was the one he visited in Peachtown, Canada, Edward Freeman Smith) and a nephew.

We now know

At least we now know who Smith was and what he did in the unstable and dangerous years of late 19th and early 20th century China—events that still echo loudly in the internal polities of modern China.

And we can write an amended version of his entry in the Eponym Dictionary of Mammals:

Smith, J.A.C.

Smith’s Shrew. Chodsigoa smithii Thomas, 1911

Smith’s Zokor. Eospalax smithii Thomas 1911

Dr. John (‘Jack’) Arthur Creasey Smith (1873-1929), born in Spalding, Lincolnshire, England was an Edinburgh medical graduate who joined Malcolm P. Anderson in 190-11 when the latter was leader of the Duke of Bedford’s Exploration of Eastern Asia for the Zoological Society of London. Both the shrew and the zokor (mole-rat) come from Central China. Smith was also a member of Harold Wallace’s expedition in 1911-12. Dr. Smith, a former medical missionary and medical officer in World War I became a ship’s doctor in the 1920s. He died in New Zealand.

|

The description of Smith's Zokor in Handbook of Mammals

of the World, Volume 7. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2017 |

|

| ...and his shrew, from Volume 8, 2018 |

And the Chinese boy?

…And what happened to the Chinese boy who Smith brought to Britain in 1903/4? Well, Mrs Johnson provided the answer but I do not know the source of her information:

…he had brought with him two Chinese boys: Li and Cheng T’en Yu. They both attended Spalding Grammar School. Li went on to Edinburgh University where he graduated as a Doctor. They both eventually went back to China and continued to have medical careers in the hospital in Xian…

——————— §§§ ———————

There are a number of unanswered questions on the Duke of Bedford’s Exploration, for example, why the expedition was tagged as the Zoological Society of London’s when it was clearly a series of collecting expeditions for Oldfield Thomas of the Natural History Museum. Having now read a considerable amount about the Exploration I am by no means certain the Zoological Society of London was involved at all. It seems to me that Malcolm Playfair Anderson and, after his death, his father, conflated the British Museum (Natural History) and the Zoological Society of London since the Duke of Bedford who paid for the Exploration was President of the latter at the time.

*The equivalent of £304,000 based on retail price index or £713,000 on increases in income (GDP/capita).

Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. 2009. The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

Bickers R, Tiedemann R.G. 2007. The Boxers, China and the World. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield

Glover R. 1914. Herbert Stanley Jenkins MD FRCS. Medical Missionary, Shensi, China. London: Carey Press.

Lo H-M (editor). 1978. The Correspondence of G.E. Morrison II. 1912-1920. Cambridge University Press