There are not many articles that can be started with the immortal line of W.S Gilbert ‘When I was a lad’. But this one can.

When I was a lad the discovery of the parathyroid glands was attributed to the Swedish anatomist, Ivar Sandström (1852-1859), of the University of Uppsala. He described these ‘new’ organs closely attached to the thyroid in man and the separate organs in the horse, rabbit and cat. Their vital function in calcium metabolism was of course unknown—Sandström thought them to be embryonic portions of the thyroid—and the name ‘parathyroid’ only came into use in 1896.

It was only gradually in the second half of the 20th century that historical discoveries published in 1953 became better known. The outcome, in short, was the recognition of Richard Owen, that great anatomist, anti-Darwinian and deceitful oleaginous creep, was the first to describe the parathyroids. Now, in contrast to 60 years ago, Owen and not Sandström appears in all the literature as the discoverer

The possibility that Sandström may not have been first was raised by the physician, Sir Humphry Davy Rolleston (1862–1944) in a book on the endocrine glands published in 1936:

The presence of what were, or may have been, parathyroids was observed by Robert Remak (1815-1865) of Berlin in 1855, by Richard Owen (1804-1892)…in 1862 in an Indian rhinoceros…and by [R.] Virchow (1821-1902) in 1863 in man.

That extract was from a chapter of a book published in 1953 and written by Alexander James Edward Cave (1900-2001). I will return to Professor Cave, who uncovered the whole story of the discovery of the parathyroids, below.

Cave established that Owen had indeed described what was later named the parathyroid glands but even so, the date given by Rolleston, 1862, for Owen’s paper would still have left Remak the probable first—in 1855. Cave, though established that Rolleston had misinterpreted the date of Owen’s publication in Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. 1862 was the date the whole volume was published but each part of the volume had previously been published separately. He explained:

The work of dissection and drawing proceeded apace during the winter months of 1849-50, and on 12 February 1850 Owen communicated the resultant monograph to a meeting of the Zoological Society. This paper was published as the third article in the fourth volume of the Society's Transactions, which volume, covering the period January 1851 to September 1862, bears the terminal date of 1862—a point which has led Rolleston and possibly others astray. For in those early days of the Zoological Society's publications, the individual papers comprising any particular volume of its Transactions appeared separately, under dates anterior to the terminal volume date. Thus Owen's rhinocerotine memoir was published, not in 1862 as commonly supposed, but full ten years earlier, viz., on 2 March 1852, a point of importance in connexion with priority in the matter of the discovery of the parathyroid glands.

Owen really had got there first and in a rhinoceros, the Indian species Rhinoceros unicornis, which had died at London Zoo.

|

| Richard Owen discovered the parathyroid gland in an Indian Rhinoceros We saw this mother and offspring Kaziranga in Assam in February 2007 |

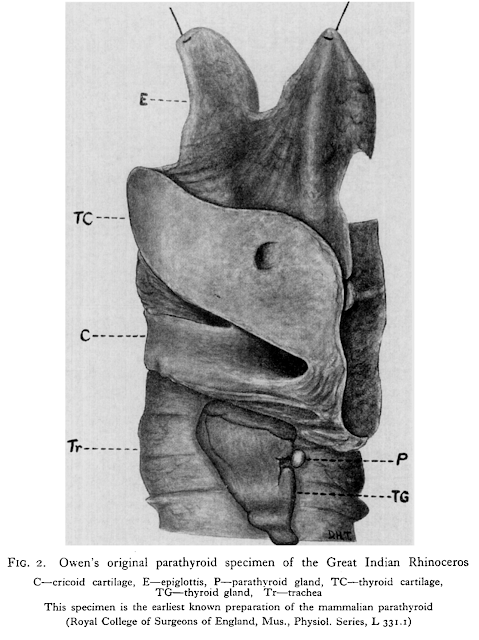

Cave himself had produced a series of papers on the anatomy of rhinoceroses which, again, like Owen, based on the dissection of animals that had died at London Zoo. He knew what he was looking for when he re-examined Owen’s descriptions. The clincher was the finding that Owen’s dissection of the thyroid region had been preserved and had survived in the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons. Cave himself had dissected the same region in the neck of two Indian rhinos that had died at London Zoo in 1941 and 1945. He knew what he was looking for and found the dissection ‘tedious and laborious’. He was full of admiration for Owen, dissecting in unknown territory but uncovering and displaying an organ ‘in diameter and circumference no greater than a sixpenny piece’ (i.e ¾ inch or 19.3 mm diameter).

|

| Cave included a photograph of Owen's dissection preserved in the museum at the Royal College of Surgeons |

Owen was dissecting the first Indian Rhinoceros to be exhibited at London Zoo. He described the animal as his ‘ponderous and respectable old friend and client’, client because he had examined the animal before its purchase by the zoo fifteen years earlier ‘and took it upon my skill, in discerning through a pretty thick hide the internal constitution, to aver that the beast would live to be a credit to the Zoological Gardens, and that he was worth the 1000 guineas demanded for him’. In present day values the price was around £100,000.

After it death on 19 November 1849 dissection of the beast, which would have weighed over 2000 kg, was done at the Royal College of Surgeons where Owen, as Conservator of the museum, had a residence. Owen’s wife, Caroline, recorded in her diary that 'as a natural consequence' of this animal's death 'there is a quantity of rhinoceros (defunct) on the premises’. She was probably inured to such matters; her father was the first conservator of the museum. And inured she probably needed to be since the rhinoceros flesh would have been putrefying after several months in the building. Although the retained specimens would have been preserved in spirit, the use of formalin for temporary preservation (as in our dogfish, frog and rabbit dissection days for ‘A’ levels) did not arrive until nearly the end of the 19th century. The only consolation for Mrs Owen is that the animal died in November and not June.

Cave ended his chapter:

That Owen was the first to describe and to preserve the gland now called parathyroid, and that he recognized its glandular nature, is sufficiently established. His discovery deserves to be more wideIy known and appreciated, not only as constituting a tribute to his acumen as an investigator, but also as redounding to the credit of British anatomical science.

The term 'parathyroid' is admittedly unsatisfactory as a descriptive label for structures which, in different mammalian species, and even in different individuals of any one species, may be indiscriminately para-, epi- or intrathyroid in position. For want of a more convenient term, and by general acceptance, this name is established and is likely to remain. At one period, however, the parathyroids were commonly known as 'Gley's glands'. Eponymous anatomical nomenclature is, unfortunately, unfashionable nowadays—to the detriment of the student's appreciation of the long, varied and educative history of the subject. But should such nomenclature achieve a return to favour, the parathyroids are already provided with their most appropriate name—‘the glands of Owen’.

Before ending this article on an endocrine gland in a ponderous pachydermatous perissodactyl it would be remiss to omit more mention of the man who discovered the discoverer, Professor Cave.

Professor Cave

A.J.E. Cave

Professor Alexander Cave was possibly the last surviving classical anatomist in Britain. Like some of his contemporaries he did not confine himself to human anatomy and in his later years made the anatomy of rhinoceroses his particular interest. He worked in London and from London and Whipsnade zoos he had over many decades a number of animals to study. However, he also sought out preserved specimens in museums and studied some aspect of the anatomy of all species. His papers on rhinoceroses can be found in full at the Rhino Research Center’s website. However, he by no means confined himself to rhinos; he wrote papers on a multiplicity of topics and species, including whales and gorillas, neanderthals and human acrobats. His final paper was published at the age of 94.

Cave was, being an anatomist then, medically qualified. From being a medical student in Manchester he moved, first to Leeds for 10 years and then to University College London. In 1935 became Assistant Conservator of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, and from 1941 held the title of Professor of Human and Comparative Anatomy. He was in post when, at 12.55 am on 11 May 1941, bombs hit the building and destroyed half of the collection of specimens. In 1946, Cave was appointed to St Batholomew’s Hospital medical school as Professor of Anatomy. There he stayed until he ‘retired’ in 1967. Students who passed through his lecture theatre, dissecting room and examination halls found him terrifying—a common trait of professors of anatomy at a time when the subject dominated preclinical medical education—but also a highly-regarded supportive figure. He is said though to have found difficulty coming to terms with the presence of increasing number of female students. After his retirement he moved his base to London Zoo where be became a willing horse, editing papers for ZSL’s scientific journals and chairing innumerable scientific meetings.

As well as wide-ranging interests in things conventionally anatomical, Cave had a deep interest in the history of the subject—as is evident from his work on ‘the glands of Owen’. He, a staunch Catholic, was also called upon to determine the authenticity of relics in various religious establishments, both Catholic and Anglican. In a report never made public or retained (except for the one copy kept by Cave) he found no evidence to support the belief that bones in a shallow grave in Canterbury Cathedral were those of Thomas à Beckett murdered in 1170. That must have come as a shock to the Dean and Chapter; they had already commissioned an architect to design a cover for the burial place. In other cases he variously decided for (the skull of St Ambrose Barlow, who was hanged, drawn and quartered at Lancaster Castle) and against (the alleged hand of St James the Great at a church in Buckinghamshire) the authenticity of other relics.

Very little was known about Professor Cave, where he came from and what he did, by younger attendees of scientific meetings at ZSL in the 1970s. He appeared, chaired the meeting with avuncular charm and sometimes misunderstanding—and then disappeared. One obituarist remarked that having been born in 1900, “he was a Victorian, and something of that period clung to him: in his dress, in his splendid use of the English language, and, yes, his gentle gallantry with the ladies”.

Having been a lay brother in a monastic order, on his second wife’s death he moved into a convent care home; there he celebrated his 100th birthday eight months before his death.

Finally, Cave complained to his opposite number at the Middlesex Hospital that his office at Barts was rather small. There was a swift rejoinder to the effect that any office would look small if it was, like Cave's, shared with the skulls of two adult rhinoceroses.

|

| Cave studied all the rhinoceros specimens he could lay his hands on This is a Black Rhinoceros we photographed in the Masai Mara in September 1991 |

Cave AJE. 1953. Richard Owen and the discovery of the parathyroid glands. In, Science Medicine and History Volume II. Edited by E Ashworth Underwood, p 217-222. London: Oxford University Press.

Cave AJE. 1953. The glands of Owen. St Bartholomew’s Hospital Journal 57, 131-133.

Cave AJE. 1976. The thyroid and parathyroid glands in the Rhinocerotidae. Journal of Zoology 178, 413-442.

Walls E. 2001. Professor A.J.E. Cave 1900-2001. Journal of Zoology 255, 283-284.

No comments:

Post a Comment