|

| I photographed this male Hong Kong Newt in 1966 in the old Northcote Science Building of the University of Hong Kong |

In the literature the Hong Kong Newt is described thus: Paramesotriton hongkongensis (Myers & Leviton 1962). Behind that simple label is the story of those not only who described the species but also of those who collected and sent the animals from Hong Kong to Stanford University in California. Nearly all the people involved have appeared in my previous articles but until last week I had not realised that I had already related some of the events that led to the Hong Kong Newt being described as a separate species.

Pre 1962: the species it was then thought to be

Before 1962 the only species of newt or salamander found in Hong Kong was lumped into Cynops chinensis originally described by John Edward Gray FRS (1800-1875) of the British Museum (Natural History) in London. The description was published in Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London in 1859 and his specimens were obtained by a Mr Fortune who brought it in a bottle along with ‘some Fishes and a Leech, collected from a river on the north-east coast of China, inland from Ningpo’. The fishes, incidentally, turned out to be domestic goldfish (the description of the tail and the large upturned eyes fits the Celestial variety). Gray called them ‘a very peculiar monstrosity’—words I cannot better. Were they really found in the same stream as the newt? Or were they all from a stream in a goldfish farm?

That species of newt was redescribed by several taxonomists over the years but all the names given were eventually regarded as synonyms of that chosen by Gray for the newt from ‘inland from Ningpo’. I shall return to Mr. Fortune in another article. I shall write it after a cup of tea and therein lies a clue.

Geoffrey Herklots in 1930s Hong Kong was keen to identify the local fauna. He sent amphibians to Alice Boring in Beijing, or what was then Peiping to most Americans and Peking to most Brits, over 1200 miles to the north, where she was collecting and identifying amphibians of northern China. She identified the newts that Herklots sent as Triturus sinensis (a name that was a synonym of Gray’s C. chinensis and therefore invalid). In her paper published in The Hong Kong Naturalist in 1934, Herklots was forced to add a note since Boring suggested it might have been introduced. Herklots had sent her 27 preserved specimens from ditches in Quarry Bay and he pointed out that the newt was common and widespread throughout Hong Kong and adjacent areas of Guandong (Kwangtung, Canton) province and, therefore, clearly native.

Myers and Leviton began their paper with:

The newt occurring on Hong Kong Island and a small part of the nearby mainland (chiefly the hills of the Kowloon area has traditionally been identified with the newt inhabiting the Ningpo region of east-central China. The latter was named by Gray (1859) as Cynops chinensis. The two forms were separated subspecifically by Herre (1939), chiefly on osteological characters, but he erred in renaming the northern form, leaving the Hong Kong population nameless.

As far as I can make out (I have not seen the original paper) that Herr Herre (for there are two in the story) named the northern form T. sinensis boringi, possibly because a student of hers had found newts identified as this species in Chekiang (Zhejiang) province which would be expected since Mr Fortune had found Gray’s type specimen in the north of that province near Ningpo (Ningbo).

Karl Wolfgang Herre (1902-1997) attracts little attention these days. The paper Myers and Leviton referred to was a survey of Asian and North American urodeles. For his PhD awarded in 1932 he worked on the subspecies of Triturus cristatus, the Great Crested Newt of Europe. He later worked at the University of Halle and, part-time, at the Natural History Museum in Brunswick. He continued to work on urodeles for most of his life including the endocrine control of metamorphosis and fossil salamanders. A biography on Wikipedia in German shows that he was a member of the Sturmabteilung—the S.A. ‘Brownshirts’—and of the Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund, NSLB—the National Socialist Teachers League—from 1934 and of the Nazi Party itself from 1937. It was during this time that he collaborated with other herpetologists in the study of newts and salamanders, including Wilhelm Georg Wolterstorff (1864–1943), a major player in research on newts and salamanders and in promoting amateur herpetology through the keeping of live animals and in linking amateurs with professional museum scientists. In 1936 Herre was co-author of a paper with Louis Lantz, the French ‘amateur’ working in Manchester. The Second World War would see the co-authors on very different sides with Lantz being the representative of the Free French Forces. Postwar we learn, ‘After military service and captivity’, Herre went to Christian-Albrechts-University in Kiel ‘in the late summer of 1945’. He became a nutritionist and deputy director of the Zoological Institute and Museum and the Museum of Ethnology. In 1947 he was appointed director of a new institute for domestic animals. There he worked on domestication, particularly of dogs.

1962. The ‘new’species

The source of the material Myers and Leviton used to erect a new species is very interesting since it involved two international networks one, prewar, in fisheries research and the other, postwar, of those interested in aquarium fish. The type specimen—the holotype—for the new species was collected by Geoffrey Herklots from a stream on the Peak of Hong Kong Island. It was given to Dr Albert William Christian Theodore Herre (1868-1962) (the other Herr Herre) who from 1928 until 1946 was Curator of Zoology at Stanford University’s Natural History Museum. Before that he had been Chief of Fisheries with the Bureau of Science in the Philippines. The date given for the addition of three other specimens added to Stanford’s collection and designated as paratypes was 1941. The man who gave the specimens to this Herre was Herklots’s close colleague S.Y. Lin (Lin Shu-Yen) (1903-1974); they co-authored a book, Common Food Fishes of Hong Kong, in 1940. Lin was the man running fisheries research in 1930s Hong Kong along with Herklots who was in charge of the biology department at the University of Hong Kong. Lin was then or became Superintendent of Fisheries Research for the Hong Kong Government. He was later recruited by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations to work in Washington DC as an expert in fresh-water fisheries and pond-fish culture. After that he worked in Taiwan in fisheries research.

What we do not know is why Lin passed specimens of the Hong Kong Newt to Herre, presumably in 1941 just before the Japanese invasion and occupation. Was Herklots keen to get another opinion as to their identity? Or was the request passed to Hong Kong from Stanford as its interests in systematics and taxonomy and its museum expanded? Was Herre visiting Hong Kong (which he had done in the 1920s) or were the specimens sent by post? There may be answers lying in archives.

The history of the live specimens sent to Stanford in the 1950s is also interesting. The paper states of one of the designated paratypes:

U 20280, female, Kowloon Mountains*, collected in January 1952, by J. D. Romer and sent alive to the senior author by Mme. Natasha de [sic] Breuil.

John Romer (1920-1982) and Natasha du Breuil (ca 1891-1966) have featured prominently in earlier articles I have written, as has George Sprague Myers (1905-1985) at Stanford.

Myers had a lifelong interest in aquaria and his professional activities in ichthyology and herpetology grew from and remained intertwined with others who kept, imported and bred fishes for the home aquarium. In that respect he worked on The Aquarium with William T. Innes and was scientific editor for the latter’s famous book, Exotic Aquarium Fishes. He also edited The Aquarium Journal.

Contact between Myers and Natasha du Breuil would have been via a worldwide correspondence group established by Gene Wolfsheimer, Aquarists' Internationale. Thanks to the activities of that group we have more information on when live Hong Kong newts were sent to Myers.

In the special Coronation Issue (June-July 1953) of Water Life magazine it was reported that Mme. du Breuil had 'achieved a successful shipment of live newts by air to Dr G Myers (U.S.A.). It is believed that this species of newt...has rarely been imported alive into the United States. The newts for the special shipment were collected locally by Mr Romer…'

Just as with the earlier passage of specimens from Herklots via Lin to Herre at Stanford, we do not know who instigated the transport of live specimens from Romer via Natasha du Breuil to Myers who worked alongside Herre at Stanford. Were the Stanford taxonomists looking for more specimens in order to work on this newt or was John Romer looking for some expert taxonomist to take a fresh look at the identity of the Hong Kong newt?

Whatever the motivation, it took ten years for the paper by Myers and Alan Edward Leviton (whose major interest was in herpetology and is now Curator of Herpetology Emeritus at the California Academy of Sciences). It is clear from the description of the new species that the live specimens sent by Natasha du Breuil were of great value. Because the coloration of preserved amphibians is changed so markedly it is difficult if not impossible to include colour in formal descriptions of dead material. Myers and Levition did include such information since Myers, at least, had seen and recorded what the live newts look like.

Telling t’other from which

Myers and Leviton compared the specimens of Hong Kong newts with Gray’s Cynops chinensis (now Paramesotriton chinensis) which is kept at the Natural History Museum in London. Gray’s account suggests Mr Fortune’s bottle contained just one individual. However, the Museum’s records show there were two and since Gray did not indicate which was the ‘type’ (holotype) they are regarded formally as syntypes, i.e. one of several specimens in a series of equal rank used to describe the new species where the author has not designated a single holotype. Myers and Leviton thanked Alice ‘Bunty’ Georgie Cruikshank Grandison (1927-2014) who was curator in charge of amphibians and reptiles at the Museum. It appears that she sent one of the two from Mr Fortune’s bottle to Stanford.

Myers and Leviton originally placed the Hong Kong Newt in the genus Trituroides. All what have come to be known as the Asian Warty Newts have more recently been placed in the genus Paramesotriton.

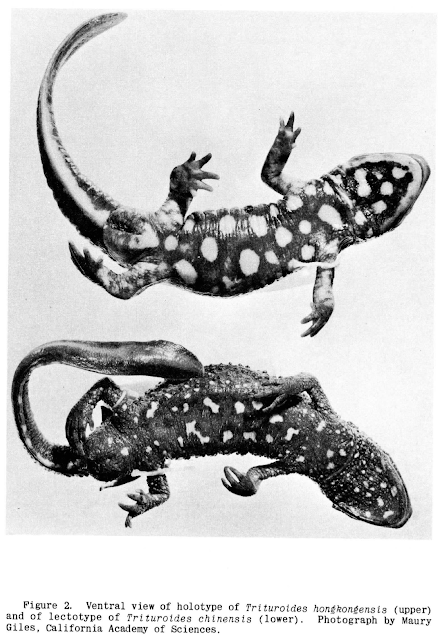

This is how they distinguished hongkongensis from chinensis:

Differs from the more northerly T. chinensis (Gray) in the much smoother, less tuberculated (versus very rough, strongly warty) skin of the head and trunk; shorter and less divergent patches of parasphenoid teeth; a broader head and interorbital region; the presence of a distinct median parietal ridge; the presence of large (versus very small) spots (red in life) on the gular region; and the presence of a continuous light (red) streak (versus an interrupted one along the inferior midline of the basal part of the tail; and much stronger dorsolateral ridges.

Apart from a table of basic measurements comparing seven Hong Kong Newts with the syntype of chinensis (no differences are apparent) the differentiation was typical of the practice of taxonomy. The comparison is purely qualitative with no attempt at quantification. Presented with a specimen of either species how would an observer know whether or not the skin was smoother or less tuberculated or the head broader?

|

| From Myers & Leviton 1962 The bottom specimen is that collected by Mr Fortune and described by Gray |

Is the Hong Kong Newt really a separate species?

The naming of the Hong Kong Newt as Trituroides hongkongensis and now Paramesotriton hongkongensis as a separate species endemic to the territory of Hong Kong and the immediately adjacent areas of Guandong province always seemed to me somewhat anomalous. Why should that tiny bit of China have a distinctive species as the only urodele in its native fauna? Could it be, for example, that there were/are undiscovered populations between Hong Kong and Ningbo and that Gray’s chinensis and hongkongensis are the two ends of a cline of one species?

As far as I understand what has happened in more recent years the Hong Kong Newt was lumped back into Paramesotriton chinensis around 1990 but then split off again more recently. At present, and supported by limited evidence from mitochondrial DNA, the Hong Kong Newt still stands as the species Paramesotriton hongkongensis. An account can be found on AmphibiaWeb here.

*Old Hong Kong residents will recognise this stated location as a problem. Kowloon Mountain (no plural) or Kowloon Peak (Fei Ngo Shan) was a specific location best described as north-east of the old Kai Tak Airport. I strongly suspect that the location given, Kowloon Mountains, should be without that final s. The mountains in mainland Hong Kong lie to in the New Territories, north of Kowloon. I am pretty sure John Romer would not have used Kowloon Mountains for a location other than Kowloon Peak. Indeed he refers to Kowloon Peak as a location for the species in his 1951 paper.

Böhme W. 1998. In memoriam Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Wolf Herre (1909-1997) - ein Zoologe mit bedeutendem amphibienkundlichen Werkanteil. Salamandra 31, 1-6.

Gray JE. 1859. Descriptions of new species of salamanders from China and Siam. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1859, 229-230, plate 19.

Herre W. 1939. Studien an asiatischen und nordamerikanischen Salamandriden. Abhandlungen und Berichte aus dem Museum für Natur- und Heimatkunde und dem Naturwissenschaftlichen Verein in Magdeburg 7, 79-98.

Myers GS, Leviton AE. 1962. The Hong Kong Newt described as a new species. Occasional Papers of the Division of Systematic Biology of Stanford University No 10, 1-4.

Romer JD. 1951. Observations on the habits and life-history of the Chinese Newt, Cynops chinensis Gray. Copeia 1951, 213-219.