When ‘Amo’ was in expansive mode the conversation at tea time was wide ranging, from what he was writing to the people (mostly old colleagues at the Royal Veterinary College) he loathed. One afternoon in the early 1970s he described how in the early 1950s he and a party had been to visit Romney Marsh each year to see and hear the introduced Marsh Frogs. I remember that he mentioned some of the people who were with him (Leo Harrison Matthews was one), that they were from the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the British Herpetological Society (BHS) and that I had later read about the trips and the people who went on them. But where had I read it and who were his other companions?

By chance I was looking through an old Bulletin of the BHS when I came across an article by John Francis Deryk Frazer (1916-2008) describing the activities of the BHS in the early years. He wrote:

At this time, parties of members used to go to see the Edible Frogs at Ham gravel pits and the Marsh Frogs in Romney Marsh. One particular group which contained Malcolm Smith, Max Knight, Jack Lester and Dr. (later Professor) E.C. Amoroso, used to have an annual trip to the Marsh to see how the frogs were getting on, which so far as I can gather was a glorified pub crawl in which Marsh Frogs were included.

Whether this was the whole group I do not know but Frazer’s recollection is wrong in one detail. Amo was already Professor of Physiology at the RVC. All the trippers were well known in the scientific and herpetological world:

Malcolm Arthur Smith (1875-1958), formerly physician to the royal household of Siam had been retired since 1925 but worked in London at the Natural History Museum; he wrote the volume on British amphibians and reptiles for the New Naturalist series in 1951 and was founding president of the BHS.

Charles Henry Maxwell Knight OBE (1887-1968) was still working for the Security Service MI5 but also becoming established as a naturalist and broadcaster.

John ‘Jack’ Withers Lester (1908-1956) was Curator of Reptiles at London Zoo and leader of the televised ‘Zoo Quest’ expeditions filmed for the BBC. In an obituary, Matthews wrote:

For several years after 1950 he and a group of friends including the late F.J.F. Barrington made one or two week-end trips to Romney Marsh to study and collect the Marsh Frog Rana ridibunda, a gathering that became known facetiously as the ‘‘Ribi Bund”. Even on these comparatively tame expeditions Jack’s splendid qualities were conspicuous—his patience and tenacity, his skill in finding and capturing the quarry, his equanimity on falling headlong into a marsh ditch in the small hours of a frosty March morning, and his good companionship on at last reaching the snug inn parlour to discuss the restoratives left out against our return.

Leonard Harrison Matthews FRS (1901-1986) was Scientific Director of ZSL from 1951.

Amo was of course Emmanuel Ciprian Amoroso, CBE, FRCS, FRCOG, FRCP, FRCPath, FRS (1901–1982).

The reader will note that a new name has now appeared in addition to those recalled by Deryk Frazer:

Frederick James Fitzmaurice ‘Snorker’ Barrington (1884-1956) was a surgeon at University College Hospital. Sir Charles Lovatt Evans, the physiologist, in an obituary wrote:

He was widely read in many directions, but especially in the biological sciences; natural history was his hobby, and he was often to be seen on Sunday mornings at the Zoological Gardens with which he became intimately familiar. Much of his spare time was occupied with research work, for which he had the gifts of penetrating observation, manual dexterity, and infinite patience. He was working in the laboratories of the Royal Veterinary College at the time of his death. His work on the neurological control of micturition, published in a series of papers from 1914 to 193, was outstanding, and, although it did not at first receive the recognition it deserved, it has stood the test of time. [Barrington is known for the eponymous structure in the brainstem, Barrington’s nucleus or the Pontine Micturition Centre.]

That pub looms large again and indeed fits the definition of ecology we propounded in the 1960s as the only useful knowledge to emerge from botany field trips:

Ecology is the study of plants and animals in warm, dry weather and within 100 yards of a public house.

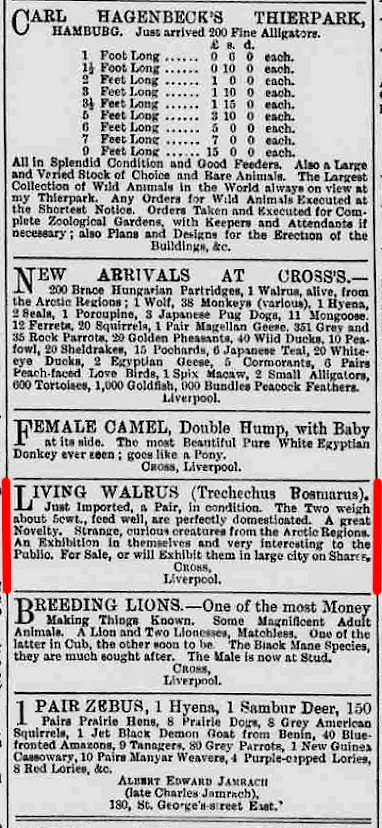

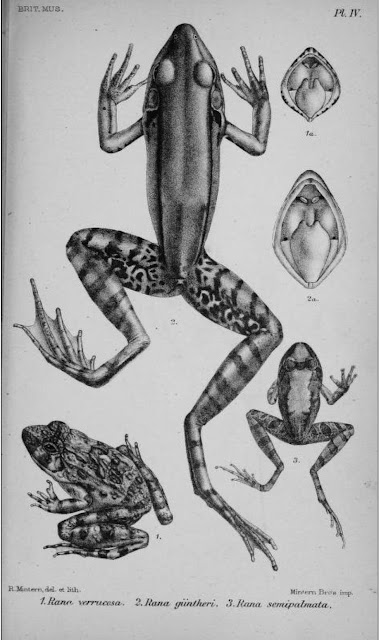

For those unfamiliar with the British herpetofauna the non-native Marsh Frog (now Pelophylax ridibundus) was introduced into a garden pond on Romney Marsh in February 1935 by Edward Percy Smith (1891-1968). That Smith, not to be confused with Malcolm Smith) wrote an account of their introduction in the Journal of Animal Ecology in 1939 while Malcolm Smith in his New Naturalist volume provided further details. In the 1930s and, indeed, until the genetics of European water frogs was sorted out in the 1960s, Marsh Frogs were often called Edible Frogs, and vice versa. Water frogs (Pelophylax) of whatever species were imported to supplement the many tens of thousands of Common Frogs (Rana temporaria) caught in Britain each year for class dissections and, when pithed, for practical physiology classes. The twelve Marsh Frogs were obtained from University College London (UCL). Edward Smith states that they had been kept in cold storage and without food for 18 months. Malcolm Smith wrote that they had just arrived at UCL from Debreczen (Debrecen) in Hungary when Edward Smith obtained them.

At the time he put the frogs in his pond Edward Percy Smith was a company director and playwright, an occupation he continued into films (The Brides of Dracula, 1960, for example) and television, usually under the name of Edward Percy. He was elected Member of Parliament for Ashford in Kent at a 1943 by-election and held the seat until 1950 when he stood down. He clearly got more than he bargained for when spring arrived. ‘For weeks on end’, he wrote, ‘nobody could sleep on the pond side of the house, and the frogs were becoming a first-class nuisance’. In June two of the largest males had moved out of the garden and into a mere about half a mile away and began calling. By October all the frogs were in the mere. A year later (1936) the mere was full of young Marsh Frogs and individuals were found three miles away. By May 1937 in what E.P. Smith described as the ‘Great Year’ there was ‘an enormous amount of spawn, and tadpoles and minute frogs were to be seen everywhere’. Frogs were seen up to 14 miles away in both directions.

Over the years the spread of the Marsh Frog has been well documented and I think it must have been the large number of frogs, their large size, their rapid expansion in number and in range as well as the incredible noise that the males make in the breeding season that drew those distinguished scientists and naturalists to Romney Marsh in the early 1950s—as well as the thought of the local hostelry.

Monitoring the population and range of the Marsh Frogs in southern England has of course continued as the range has expanded northwards and other, possibly unrelated, colonies have been discovered. It did not go unnoticed that with such a small founder population a loss of genetic diversity and therefore the deleterious effects of inbreeding might have been expected. However, Inga Zeisset and Trevor Beebee found a similar degree of genetic diversity in the Kent population to that in Hungary and just as in other introduced species throughout the world whose populations boomed immediately there was no sign of a genetic bottleneck.

Two schools of thought emerged on the introduction of non-native amphibians and reptiles. The first was that the last Ice Age and the formation of the English Channel left the British Isles so impoverished in number of species that species found in continental Europe bounded by the North Sea and the English Channel should be given a helping hand to fill what were presumed to be empty ecological niches. Deliberate release was not involved in many cases because just as with the Marsh Frog colonies of escaped animals became established sometimes for a short period but others that persist to the present day. The view that we should allow the presumed empty niches to be refilled still persists but release has been illegal since 1981. The opposite view invokes the precautionary principle: that all non-native animals are potentially invasive and damaging to the native fauna and flora. The latter group has the accommodationists and the eradicators, the latter advocating the extermination of introduced species regardless of a demonstration of ecological damage. Whatever the views, and whatever the evidence of possible competition with Common Frogs or predation of other wildlife, there is no doubt that the descendants of Edward Percy Smith’s Marsh Frogs are here to stay. By sheer chance they found themselves in an ideal habitat.

Finally, there is so much wrong information on the origins of the Marsh Frogs on Romney Marsh that I can only conclude that even so-called local experts have not read the original descriptions or even noted the correct date. Read at your peril. I did though enjoy this short video by Paul Bunyard:

Beebee TJC, Griffiths RA. 2000. Amphibians and Reptiles. A Natural History of the British Herpetofauna. London: HarperCollins.

Frazer D. 1983. The British Herpetological Society—a reminiscence. British Herpetological Society Bulletin No 8 December 1983, 10-12.

Frazer D. 1983. Reptiles and Amphibians in Britain. London: Collins

Smith EP. 1939. On the Introduction and distribution of Rana esculenta in East Kent. Journal of Animal Ecology 8, 168-170.

Smith M. 1951. The British Amphibians and Reptiles. London: Collins

Zeisset I, Beebee TJC. 2003. Population genetics of a successful invader: the marsh frog Rana ridibunda in Britain. Molecular Ecology 12, 639-646.