Not content with gross anatomical description, Joan Procter threw whatever modern technique she could find to discover as much as she could about the Pancake Tortoises, now known as Malacochersus tornieri, sent to London by Arthur Loveridge, the dead ones at the Museum and the live ones at the Zoo. She used X-rays and fluorescent screen x-ray equipment provided by the surgeon Sir John Bland-Sutton (1855-1936) of the Middlesex Hospital. He was a keen supporter and vice-president of the Zoological Society of London. She collaborated with Richard Higgins Burne (1868-1953, elected FRS 1927) who was Physiological Curator at the Royal College of Surgeons on the structure of the jaw. Burne was also a key member of the Zoological Society in the 1920s and 30s.

Boulenger had commented on the first specimens sent by Loveridge to confirm the pliable nature of the carapace and plastron. Instead of solid bone underlying the epidermal shields as in other tortoises, Joan Procter found areas with no bone at all, especially, as suggested by Loveridge in the centre of the plastron. Deep sutures between the shields also indicated a marked degree of mobility.

|

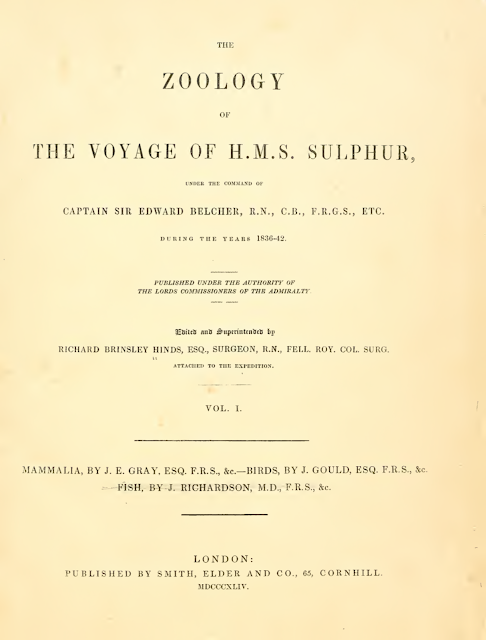

Figures from Joan Procter's paper showing the bony

carapace with the large areas (hatched) lacking bone |

|

The bony plastron showing the lack of bone in the

large central area |

In all, Miss Procter was able to work on 23 dead specimens, preserved in spirit, as well as handling the two live ones at the Zoo. Another unusual feature, apart from the areas of the carapace and plastron without bone, the tortoise is the appearance of teeth on both jaws. These teeth which are not true teeth are part of the jawbones with an overlying continuous horny sheath.

By studying young specimens and comparing the development of the carapace and plastron in other tortoises she concluded that the adult Pancake Tortoise resembles to a great extent the young of other species in which the bone then continues to grow and fill the gaps. In other words, the fenestration seen in the adult is caused by arrested development of the bony shell rather than by breakdown of a complete bony structure.

Procter noted the great variability in the shells of the Pancake Tortoise—the subject of a recent paper describing the variation between individuals in more detail.

A question that Joan Procter addressed, whether the bone of the carapace is derived from the skeleton or from the skin I will not deal with further here but will return to in the future since the question has been the subject of research for getting on for two centuries and there is recent work suggesting that old views are wrong. However, before turning to a functional problem it is worth considering how Procter argued on the mechanism evolution of the shell of the Pancake Tortoise. It is difficult for those of us who first got to know the history of theories of evolution in the 1950s to appreciate just how common Lamarckian explanations were in the 1920s or of how powerful and combative some of the individuals like Ernest MacBride FRS, who rejected both natural selection and modern genetics until his dying day, were in the zoological circles of London. Joan Procter sat on the fence:

It can be argued on the one hand that the flattened carapace is brought about by the habit of living beneath stones and squeezing into rock-crevices. This habit, induced by environment, would be bound to have a modifying effect; for, during youth, the development of a domed and solid carapace would be interfered with by the constant application of pressure, and in a sufficient number of generations the ability to form a normal carapace might be lost altogether. The fact that the Burrowing Tortoise, T. polyphemus, has a thin or fenestrated and somewhat flattened carapace supports this view. Could this be proved experimentally, it would furnish a convincing argument in favour of the heritance of acquired characters.

On the other hand, it can be equally well maintained that an inherited tendency to the arrest in development is orthogenetic, brought about either gradually or as a mutation, and that the furtive habit of hiding beneath stones was the natural result, since the tortoise no longer possessed adequate protection from enemies.

Possibly both principles come into play, the reduced armour and loss of ribs being orthogenetic, and the depression and relative condition of the vertebrae being subsequently induced by the rockdwelling habit.

Apart from the developmental origin of the bony shell, the subject that has stirred interest in the Pancake Tortoise has been the question of ‘inflation’.

The suggestion that Pancake Tortoises inflate to jam themselves more effectively into crevices between rocks came from Loveridge (see previous post of 22 November 2018):

The tortoise takes full advantage of this flexibility, as I soon found on trying to remove one from beneath a boulder. It inflated its lungs sufficiently to obtain additional purchase against the roof and floor of its retreat and, bracing its strongly clawed feet—some of the claws were over half an inch long—used them as struts so as to render its extraction extremely difficult.

Joan Procter described the animal’s characteristics thus:

In general appearance it looks as if it had been crushed in youth and had only survived by a miracle. When taken in the hand alive it has a boneless feeling which is uncanny; both carapace and plastron react to pressure on the abdominal region with a springy motion, and the animal is able to inflate itself to a slight degree.

The key question, does the Pancake Tortoise inflate itself and thereby jam itself into a space between rocks, was tackled by Leonard Ireland and Carl Gans (1923-2009), then of the University of Michigan; their paper was published in 1972. They noted that only Robert Mertens, in a paper published in wartime Germany, had questioned the occurrence of inflation: wedging yes; inflation no, he had concluded.

|

| Carl Gans |

The background to their work was that Gans had recently worked with George Hughes (1925-2011) in Bristol to sort out the method of respiration in the Spur-thighed Tortoise, Testudo graeca, itself then a matter of controversy. This tortoise and other chelonians were found to draw air into the lungs using muscles that acted in a manner akin to a diaphragm in mammals but acting within the confines of a fixed frame, the shell. There was no mechanism to force air into the lungs (as in frogs, for example). To Ireland and Gans it seemed unlikely that inflation of the body occurs during a threat. They monitored the pressure in the lungs of the Pancake Tortoise while trying to pull it backwards out of an artificial dark crevice 10 mm higher than the depth of the shell. The tortoises attempted to dig their claws of their forelimbs into the floor and rotated their forelimbs outwards. Those actions raised the front of the body and wedged it in place. The hind limbs were stretched out to the rear such that the claws tended to engage in any irregularities in the floor. The authors remarked that the wedging action was most effective; they gained the impression that the forelimbs would have to be broken before the tortoise could be pulled free of a rocky crevice in the wild. At no time during this pulling and wedging in response did pressure within the lungs rise consistently. There was no inflation. Wedging was purely mechanical and achieved by the positioning of the limbs.

Although inflation of the body cavity appeared to have been excluded as part of the mechanism by which the Pancake Tortoise wedges itself into rocky crevices or under boulders of the kopjes on which it lives, that knowledge never found itself into much of the popular literature or have reached what was then the more scientifically-isolated world of the museums. Books and papers still appeared without any reference to the work of Ireland and Gans. Some make it appear that the degree of inflation is enormous, with the impression created that the tortoise is the next best thing to a puffer fish.

However, was the wedging action of the limbs shown by Ireland and Gans the only way the Pancake Tortoise can fasten itself into crevices? Their test apparatus was arranged such that the ceiing was 10 mm greater than the height of the tortoise’s shell. Calculating the depth (i.e. the distance between the outsides of the plastron and carapace) from the photograph they show and the approximately median length of the carapace of the animals they studied, any ‘bulge’ from inflation would have to reach a 23% increase in the depth between plastron and carapace in order to reach the ceiling of the artificial crevice, a surely impossible ask.

The wedging action also leaves the limbs exposed. While offering protection in a relatively wide crevice, would it not be better to seek a narrower crevice in which the legs and head could be withdrawn. In those circumstances, movement outwards of, say, the soft area of the plastron by only a millimetre or so would really jam the tortoise in place. This is the mechanism proposed by Moll and Klemens in a paper published in 1996 but which I have not yet seen. They suggest that drawing the legs into the shell can ‘inflate’ the soft area of the plastron thus supporting the original observations of Loveridge in the field and of Boulenger and Procter in the museum and zoo. How would that work and can predictions be made that could be tested experimentally?

Respiration in tortoises is very different to the process in other land vertebrates. The lungs are attached to the carapace and are inflated and deflated by a diaphragm-like structure separating the lungs from the other internal organs. As the limbs are withdrawn into the confines of the shell there is additional inward pressure on the body cavity and, indeed, movements of the limbs are known to take part in the movement of gases into and out of the lungs. For sufficient pressure to be built up inside the body cavity to push upon the gap in the plastron the lungs would also need to be full or probably very nearly full of air. The flow of air outwards from the lungs in response to strong and sustained withdrawal of the legs and head would have to be stopped. The other alternative to stopping the outflow from the lungs would be for the lungs to be emptied completely by the build-up of pressure in the body cavity. Because tortoise lungs are so large and so capacious it seems unlikely that the decrease in volume of the body cavity would be sufficient for the lungs to be emptied and for the the covering of the plastron to be pushed outwards.

Proceeding on the assumption that the lungs are held full or close to full, the most likely scenario is that the glottis is closed and that the pressure of gases inside the lung increases, as assumed by Ireland and Gans. The other possibility, that the ‘diaphragm’ between the lungs and the rest of the body cavity is held tight such that fluid pressure changes are not transmitted to the lungs seems unlikely since that membranous diaphragm would appear to be much more compliant than the horny layer overlying the ‘hole’ in the plastron.

If this mechanism, the movement outwards of the leathery centre of the plastron brought about by withdrawal of the legs and neck, does operate the corollary is that the tortoise ceases to breathe. And here we come to the known ability of tortoises to hold their breath for long periods. As anybody who has tried to anaesthetise a chelonian using a gaseous anaesthetic will affirm, the tortoise usually remains unanaesthetised by simply holding its breath for tens of minutes while keeping its legs and head drawn into its shell. I have seen such a tortoise after about 30 minutes suddenly thrust its head out and forcibly exhale, and I do mean forcibly. The sudden exhalation was as if pressure was first applied to the lung and then the glottis opened. The best analogy I can think of is the movement down the runway of an aeroplane first held in check by the brakes until the engines reaches full power.

Other factors would come into play. Terrestrial tortoises have large bladders. If full, less inward pressure would be needed on the body cavity from the active pulling inwards of the legs and head; if empty, more. The legs and head would have to virtually seal the gap between carapace and plastron, otherwise the soft skin would be expected to bulge outwards rather than leathery plastron.

This latter point brings me to suggest that an experimental test of the bulging plastron hypothesis is needed; in other words an extension of the approach of Ireland and Gans to see what happens in narrower crevices. I am not entirely convinced by the present arguments in favour. The reason I suggest more work is needed hinges on the properties of the horny material that covers the large hole in the bony plastron. The late bob Davies had a pair of Pancake Tortoises in the early 1990s. When I handled them, I found the horny covering of that hole to be thick and relatively inflexible. However, there was ‘give’. A slight push on the centre would move it inwards by a few millimetres—the ‘springy motion’ described by Procter when she handled the first living examples at the Zoo. The question of whether sufficient pressure can be exerted on the body cavity to make that horny material bulge outwards even by a few millimetres needs to be answered.

Ireland L, Gans C. 1972. The adaptive significance of the flexible shell of the tortoise, Malacochersus tornieri. Animal Behaviour 20, 778-781.

Mautner A-K, Latimer AE, Fritz U, Scheyer TM, 2017. An updated description of the osteology of the Pancake Tortoise Malacochersus tornieri (Testudines: Testudinidae) with special focus on intraspecific variation. Journal of Morphology 278, 321-333.

Procter JB. 1922. A study of the remarkable tortoise, Testudo loveridgii Blgr., and the morphology of the chelonian carapace. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1922, 483-526.