Graham Scudamore Percival Heywood’s name appears as a regular contributor to, and as assistant editor of, The Hong Kong Naturalist, published from 1930 until the Japanese invasion in 1941.

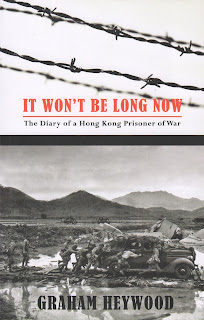

Graham Heywood has appeared in print again recently with the publication of his diary as a prisoner of war from December1941 until the capitulation of Japan in August 1945 and his return to U.K.

Heywood was a meteorologist. From 1932 until 1941 he was Professional Assistant at the Royal Observatory, Hong Kong. Educated at Winchester and Oxford, he was awarded that rare Oxford degree, the B.Sc. No longer awarded, and unlike the B.Sc. from other universities, it was a postgraduate research degree, the equivalent of an M.Sc. It should be borne in mind that a Ph.D. or D.Phil. was then not a popular route to a higher degree and often derided as ‘the German degree’.

|

| G.S.P. Heywood |

Meteorology has played a vital part in the life of Hong Kong since 1883 when the Observatory was established by the Hong Kong Government in response to a proposal by the Royal Society “for the study of meteorology in general and typhoons in particular”. Its first job was to provide early warning of typhoons to local mariners. This was not meteorology for deciding whether tomorrow will be too wet for fair-weather golfers but as a matter of life and death. Gwulo, that excellent website on old Hong Kong, recently showed photographs and reproduced articles on the typhoon of September 1874. I count about 35 vessels sunk, wrecked, run aground or missing in the early press reports, with about 2000 people killed. Warnings of approaching typhoons have been and still are taken very seriously in Kong Kong.

Heywood’s articles in The Hong Kong Naturalist cover weather observations, meteorological and astronomical phenomena, as well as accounts of hill walks, geographical features and of birds seen. Describing the passage of a typhoon on 23 November 1939, the eye of which passed directly over the Observatory, he wrote:

The calm centre of “eye of the storm” lasted from 4.05 to 4.20 p.m. at the Observatory [then, as now, just along from the Peninsula Hotel at the tip of Kowloon]. Though most people would not consider it particularly pleasant to find themselves in the centre of a typhoon, for a meteorologist it is a chance of a lifetime. Some extremely interesting observations were made…

Earlier he wrote:

Just before sunset on November 30th [1934] the interesting phenomenon of a red rainbow was seen. Some drizzle was falling at the time, and the rainbow appeared as a reddish arc without any trace of the other colours of the spectrum. The sun was close to the horizon and red in colour, consequently the light which fell on the raindrops lacked the blue and violet part of the spectrum.

His book, Rambles in Hong Kong, was published in 1938.

The story of how the diary came to be published as It Won’t Be Long Now in 2015 by Blacksmith Books is told in a Foreword by the present Director of the Observatory, Shun Chi Ming, who was shown a copy of the manuscript by one of his predecessors, John Peacock, on a visit to U.K. Thanks to Heywood’s daughter, Veronica and the widower of his elder daughter, Susan, and then with the help of Geoffrey Emerson, author of a book on the civilian internment camp at Stanley, as editor, and a number of volunteers, photographs were gathered to illustrate a publication. Then in early February 2015, a meeting with Pete Spurrier of Blacksmith Books was held. He agreed there and then to publish the book and with the speed that so characterises the way things are done in Hong Kong it was published—within just a few months.

Secret orders were opened at the Observatory as the Japanese invasion began. The magnetic station at Au Tau, a village deep in the New Territories was to be dismantled and the equipment brought back to Kowloon. He and a colleague, Leonard Starbuck, set off in two cars, crossing the British defence positions, Gin Drinkers’ Line, to reach the northern New Territories. As they were preparing to leave after dismantling the equipment they were surprised and captured by Japanese soldiers who had crossed the Shum Chun (Shenzen) River. They were treated as Prisoners of War, i.e. military prisoners, rather than being interned as the civilians they were. The diary describes the years spent imprisonment in Sham Shui Po Camp, the effects of undernutrition and malnutrition, and the effects of incarceration on the inhabitants, as well as of the attitudes of the Japanese guards. It adds considerably to the history of the occupation of Hong Kong and the events between surrender and the arrival of Rear-Admiral Harcourt’s fleet (which Heywood saw as he travelled to see the civilian internees at Stanley) on 30 September 1945. When the war ended, Heywood, after suffering malaria and malnutrition, had been working as a batman to a blind officer in the military hospital housed in the Central British School, which post-war became the King George V School.

Within a few days, as Kowloon came under British control, he was back working at the Observatory, trying ,with his colleagues Starbuck and B.D.Evans, the Director who had been interned at Stanley, to sort out the mess. Two weeks later, Heywood was on board HMS Glengyle, which had brought 3 Commando to Hong Kong, bound for Colombo and home.

Meanwhile, Mrs Heywood and daughters had been on the move. Under the threat of Japanese invasion, the Hong Kong Government arranged the evacuation of wives and children. Heywood escorted his wife and daughter to Australia and then returned to the Observatory. Hearing of the attack on Darwin in February 1942, Mrs Heywood decided she would be better returning to U.K. than facing a Japanese invasion of Australia. She was therefore there to meet her husband as he returned from Hong Kong. By then he was on board RMS Maloja. He received a cable at Port Said telling him to look out for a bunch of yellow chrysanthemums on the quay at Southampton. This brilliant signal enabled him to spot his wife as thousands of men crowded the rail on one side of the ship.

He remained an employee of the Observatory (his wife had received his pay throughout) and like many of those evacuated, he returned to Hong Kong in 1946, this time as Director. There he remained until he retired in 1955. His book, Hongkong Typhoons, was published in 19501.

The present book notes that he and his friend, G.A.C. Herklots, would lead plant-hunting and bird-watching expeditions into the hills. Herklots by that time was Secretary for Development, head of the predecessor office that became the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Herklots also gets a mention in the diary, although not referred to by name. On his trip to Stanley, when he saw the fleet entering the harbour, he recounted:

Accounts of life in the internment camp differed widely. One friend, an enthusiastic biologist, was full of his doings; he had grown champion vegetables, had seen all sorts of rare birds (including vultures, after the corpses) and had run a successful yeast brewery. Altogether he said, it had been a great experience … a bit long, perhaps, but not bad fun at all.

Another ended up her account by saying “Oh Mr Heywood, it was hell on earth”.

It all depended on their point of view.

Graham Heywood died, aged 81, on 23 January1985 in Hampshire.

|

| Sketch by Heywood |

———————

1 Heywood’s papers on meteorology in Hong Kong can be found here on the Observatory’s website.

Greetings, many thanks for your splendid article about my father. I have been invited to reminisce about my HK Observatory childhood, as part of its 140 anniversary celebrations. Chi ming Shun and Geoffrey Emerson have arranged a tightly knit itinerary, amongst which are a visit to the site of the Magnetic Station where my father and Len Starbuck were captured and I'm to lay a wreath at the Cenotaph to commemorate all who suffered as POW's during the Japanese Occupation.

ReplyDeleteWith my respect and best wishes

from Veronica Heywood

Greetings, many thanks for your splendid article about my father. I have been invited to reminisce about my HK Observatory childhood, as part of its 140 anniversary celebrations. Chi ming Shun and Geoffrey Emerson have arranged a tightly knit itinerary, amongst which are a visit to the site of the Magnetic Station where my father and Len Starbuck were captured and I'm to lay a wreath at the Cenotaph to commemorate all who suffered as POW's during the Japanese Occupation.

ReplyDeleteWith my respect and best wishes

from Veronica Heywood